The Ring Sword

An ancient Germanic memory preserved in Norse mythology

Norse mythology didn’t appear in a vacuum. The stories that have been passed down to us in Eddas and sagas generally reflect a late, Icelandic flavor of broader Germanic mythology that evolved over several millennia out of even earlier Indo-European traditions.1

We can pretty confidently date many of our mythological sources based on linguistic markers and, among these, some originated in the Viking age and others were composed sometime after. But lately I’ve been looking through them for little hints at memories passed down from an even earlier time.2

Here’s a fun one:

Christopher Sapp dated the poem Helgakviða Hjǫrvarðssonar3 in the Poetic Edda to the second half of the 10th century. It is perhaps a little less than 100 years older than the canonical “end” of the Viking age which spanned, in traditional terms, from the attack on Lindisfarne in 793 AD to the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066 AD. In this poem, our hero Helgi is given his name by the valkyrie Svafa who also tells him the location of a magic sword:

Sverð veit ek liggja í Sigarshólmi, | fjórum færi en fimm tøgu; | eitt er þeira ǫllum betra, | vígnesta bǫl ok varit gulli. | Hringr er í hjalti, hugr er í miðju, | ógn er í oddi þeim er eiga getr; | liggr með eggju ormr dreyrfáðr, | en á valbǫstu verpr naðr hala.

I know (of) swords lying on Sigarsholm, four fewer than fifty; one of them is better than all, a bale of battle-brooches4 and gold-adorned. A ring is in the hilt, courage is in the middle, fear is in the point for whoever gets to own it; a blood-stained serpent lies along the edge, and upon the “valbost”5 an adder tosses its tail.

What caught my eye here is the description of a ring in the hilt. Why would there be a ring in the hilt, you ask? Because this is a reference to a Migration-Period, Germanic ring-sword, of course!

Another reference to such a sword can be found in stanza 68 (Pettit’s organization) of the poem Sigurðarkviða in skamma, but before I relate that stanza here, it is necessary to lay out some context in order to make clear exactly which sword is being referenced.

One of the most prominent tales in Norse mythology revolves around the pre-Viking-Age hero Sigurd and his family. A compiled version of their story spanning many generations has been passed down to us in the form of the famous Vǫlsunga saga, although this saga is but a single telling of a story which seems to have been constantly reworked over time through myriad poems dealing with different saga events.

In the story as we have inherited it, the Norse god Odin gifts a sword to Sigurd’s father Sigmund in an episode that kicks off years of betrayal, blood, and vengeance. The sword is ornately decked in gold and is the finest sword anyone has ever seen. Although this isn’t stated explicitly, owning the sword appears to make Sigmund invincible in battle because, once he becomes old, Odin must appear on the battlefield to personally break the sword, thus allowing Sigmund to finally be killed and harvested for Valhalla. The broken pieces of the sword are later given to his son Sigurd who has them reforged by a master smith named Regin. At this point the sword is given the name Gram (O.N. gramr) and is used by Sigurd to slay the dragon Fafnir. Having slain the dragon, Sigurd discovers the resting place of a sleep-cursed valkyrie named Brynhild and awakens her by using Gram to cut open her physically constricting armor. (Sleeping Beauty, anyone?)

It is at this point that the details of the story become muddy due to the copious number of poems composed about Sigurd and Brynhild. However stanza 68 of Sigurðarkviða in skamma describes a scene wherein the two must sleep together in the same bed and Sigurd places his sword between them as a symbol of chastity:

Liggi okkar enn í milli málmr hringvariðr, | egghvast járn, svá endr lagit, | þá er vit bæði beð einn stigum | ok hétum þá hjóna nafni.

May ring-adorned metal lie in between us, sharp-edged iron, as in old times laid, when we both then stepped into one bed and were called then by the name of married couple.

Indeed references to ancient, powerful ring-swords are not solely confined to the Old Norse corpus. Consider the following passage from the Old English poem Beowulf lying between fits 1557-1567:

Geseah ða on searwum sigeeadig bil, | eald sweord eotenisc ecgum ðyhtig, | wigena weorðmynd; ðæt wæs wæpna cyst, | buton hit wæs mare ðonne ænig mon oðer | to beadulace ætberan meahte, | god ond geatolic, giganta geweorc. | He gefeng ða fetelhilt, freca scyldinga, | hreoh ond heorogrim, hringmæl gebrægd. | Aldres orwena, yrringa sloh | ðæt hire wið halse heard grapode | banhringas bræc; […]

A victory-prosperous sword appeared then among the war-gear: an old, ettinish6 sword of doughty7 edge, a hero’s honor; it was choice among weapons, but it was more than any other man would be able to carry into battle-play, good and adorned, a work of giants. He took then the belted hilt, the Scyldings’ warrior, fierce and savage, a ring-token unsheathed. Life despairing, angrily (he) struck; it groped hard against her neck; (her) spine broke; […]

In Old English (especially Beowulf), the sword itself is often identified by its most prominent characteristic: the ring. This type of identification still exists in Modern English wherein a “sabertooth” is neither a saber nor a tooth but a large feline with prominent saber-like teeth. Likewise a hringmæl (ring-token) is neither a ring nor a token, but a sword with a prominent ring-token affixed.

Vladimir Vasilev notes in his dissertation8 that the ring-sword carries a similar symbolism as the finger-ring, the arm-ring and the shape of the circle itself, which is that of permanence and the ever-turning natural cycles of death and renewal. Rings of various kinds (presumably including sword rings) were traditionally given out by Germanic rulers as gifts symbolizing honor-bound loyalty or as rewards for courageous or faithful service. With that in mind, it should not be surprising that ring-swords have only been found within the graves of the rich aristocracy, but never in the graves of kings (as ring-givers) themselves.9 It is also no wonder that a ring attached to one of these special swords can be called a ring-mæl (mæl being the same word used in Old English when describing certain important symbols such as the “sign” of the cross), assuming we are correct that it exists as a token of the bond between giver and receiver.

It should be noted that even though ring-swords are mentioned in literature dating to the Viking Age, the swords themselves are older. No ring-swords forged in the Viking Age have ever been discovered. Rather, they are very much a trend of the Migration Period (commonly thought of as spanning from about 375 AD when the Huns appeared in Europe until as early as 568 AD in some estimates or as late as 800 AD in others). Corresponding with the fall of the Western Roman Empire, this period saw the migrations of various Germanic peoples across Europe. Visigoths ended up in modern Spain, for example. Angles, Saxons, and some others ended up in Britain.

The ring-sword design first seems to have appeared on the scene around the late 400s among the Germanic Franks10 before quickly spreading into Scandinavia and into England by way of the Anglo-Saxon migrations. The trend reached peak popularity in the 500-600s before falling out of style entirely prior to the beginning of the Viking Age. The fact that these swords continue to be mentioned in literature composed centuries later is nothing short of amazing.

Ring-swords (apart from Gram) do tend to appear in literature among old, forgotten caches of items. Old Norse tales quite frequently describe goods (and swords in particular!) being robbed from the burial mounds of the rich and famous. In pop culture, this idea leads to Amleth’s retrieval of a ring-sword from a burial mound in Robert Eggers’ film “The Northman.”

It is probably not crazy to believe that the people of post-Migration-Period centuries could have stumbled upon and marveled at these ancient swords on occasion, thus helping to keep the memory alive. There may even have been a few still floating around as heirlooms and/or ritual objects in these later years.

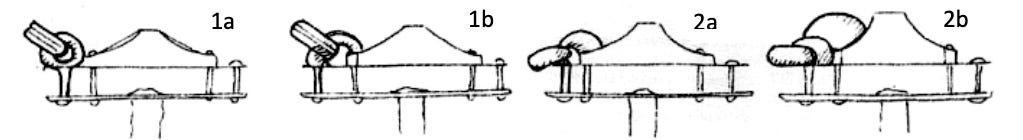

Returning to the notion of the ring as a ritualistic symbol, historical finds paint a picture of hilt-mounted rings becoming more symbolic in form over time. Vasilev provides a diagram detailing the four recognized categories of Germanic ring-swords, which happen to fall along rough geographical and chronological lines:

Type 1 mountings make use of real rings whereas type 2 are characterized by “pseudo-rings” (abstract disc shapes reminiscent of type 1). Type 1a is the earliest and rarest type, and it utilizes a free-floating ring while type 1b still retains a true ring but prevents motion by welding it into place. Type 2a is a simple pseudo-ring design that often still retains an opening somewhere in the mounting while type 2b is comprised of massive, fully abstract, often solid gold components. Outside of 2b, the various components of the ring and mounting are typically crafted from bronze, gilded bronze, or silver.11 There is one fascinating outlier from Snartemo, Norway dated to the early 6th century whereupon the ring is mounted to the crossguard rather than the pommel. At first glance one wonders about the practicality of such a design when it comes to real combat:

Ring swords have been found all throughout ancient Germanic territory and even in Finland, and their ritual importance has been preserved in ancient artwork as well. Two prominent examples come from the Gutenstein Scabbard and the Torslunda Plates.

The Gutenstein Scabbard is, as it sounds, a sword scabbard dated to the 7th century and discovered near Sigmaringen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The scabbard features a bronze relief that includes a panel depicting a man, presumably in wolf-costume, holding a ring-sword. The Torslunda plates are a set of bronze dies found in Öland, Sweden, dated to between the 6th-8th centuries, likewise featuring men in animal-themed attire, one of whom sports another ring-sword.

It is impossible to know exactly what sorts of rituals may have surrounded the bequeathing of ring-swords, or perhaps rings intended for swords. It is also nearly impossible to resist the temptation of at least surveying the landscape of symbols surrounding them:

We have Odin as a king, kings (including Odin) as ring-givers, Odin’s mythological ownership of two wolves as symbols of battle-beasts, Odin’s gifting of a (ring?-)sword to Sigmund who later spends time transformed into a wolf12, men pledged to kings as owners of ring-swords, and men holding ring-swords dressed in wolfish attire. It is easy to start imagining some ritual wherein a king, symbolizing Odin, bequeathes a ring-sword to a loyal thane dressed in wolf-attire illustrating his pledge to serve as a battle-beast for the king, symbolically as one of Odin’s wolves13. Unfortunately this ritual is nothing more than a product of my own imagination and will have to remain so until more information is discovered that might corroborate it.

The mind does run wild though, doesn’t it?

For more information, see my post “Norse vs. Germanic”.

On a related topic, I recommend the post “Shared Germanic poetic formulae” by Konrad Rosenberg.

Sapp, Christopher D. "Relative sá and the dating of Eddic and skaldic poetry" in Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax, no. 102, 2019, pp. 18-44.

Pettit notes that this particular phrasing is not perfectly clear. What I have translated here to “battle-brooches” (shields) could alternatively be “battle-fastenings” (armor) or “battle-needles” (swords). See Pettit, E., trans., The Poetic Edda: A Dual Language Edition, (Open Book Publishers, 2023), p. 429.

The Old Norse word valbǫstu does not have a clear and obvious translation though it is certainly some part of the sword. Pettit suggests perhaps the hilt binding (p. 429).

Old English eoten is the direct equivalent of Old Norse jǫtunn. The tradition of these powerful, supernatural beings was not confined only to Norse mythology, but was apparently shared among various ancient Germanic traditions.

i.e., bold, brave, valiant, etc.

Vasilev, V. “The role of ring-sword of the aristocracy in Early Middle Europe,” (SWU “Neofit Rilski”, Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria, 2018).

Vasilev, p. 5.

Oakeshott, Ewart. Sword in Hand: A Brief Survey of the Knightly Sword. Arms & Armor Inc., 2000. pp. 23-24.

Vasilev pp. 2-3.

Vǫlsunga saga contains an episode wherein Sigmund and his son Sinfjotli come across two men possessing both gold rings and wolf-garments of some kind. By donning these garments, Sigmund and Sinfjotli are transformed into real wolves for the following nine nights. During this time they fight each other and Sinfjotli is severely injured. Odin then symbolically delivers a message to Sigmund explaining how to heal Sinfjotli of his injuries.

Note also that another of the Torslunda plates features a man in wolf-attire with a hand on his sword-hilt standing behind another figure, apparently dancing, and wearing a headdress ornamented with two ravens. The dancing figure is often interpreted as symbolizing Odin, especially since laser scanning was able to determine that one of its eyes had been deliberately struck out. (Arrhenius, Birgit & Freij, Henry (1992). "'Pressbleck' Fragments from the East Mound in Old Uppsala Analyzed with a Laser Scanner". Laborativ Arkeologi. Stockholm University (6): 75–110.)

Great article

Great essay, I love that in this sword-essay you touch upon the Volsunga Saga, it is one of the most brutal, evocative and inspiring tales in history. I hope you don't mind my asking if it is one of your favourites?