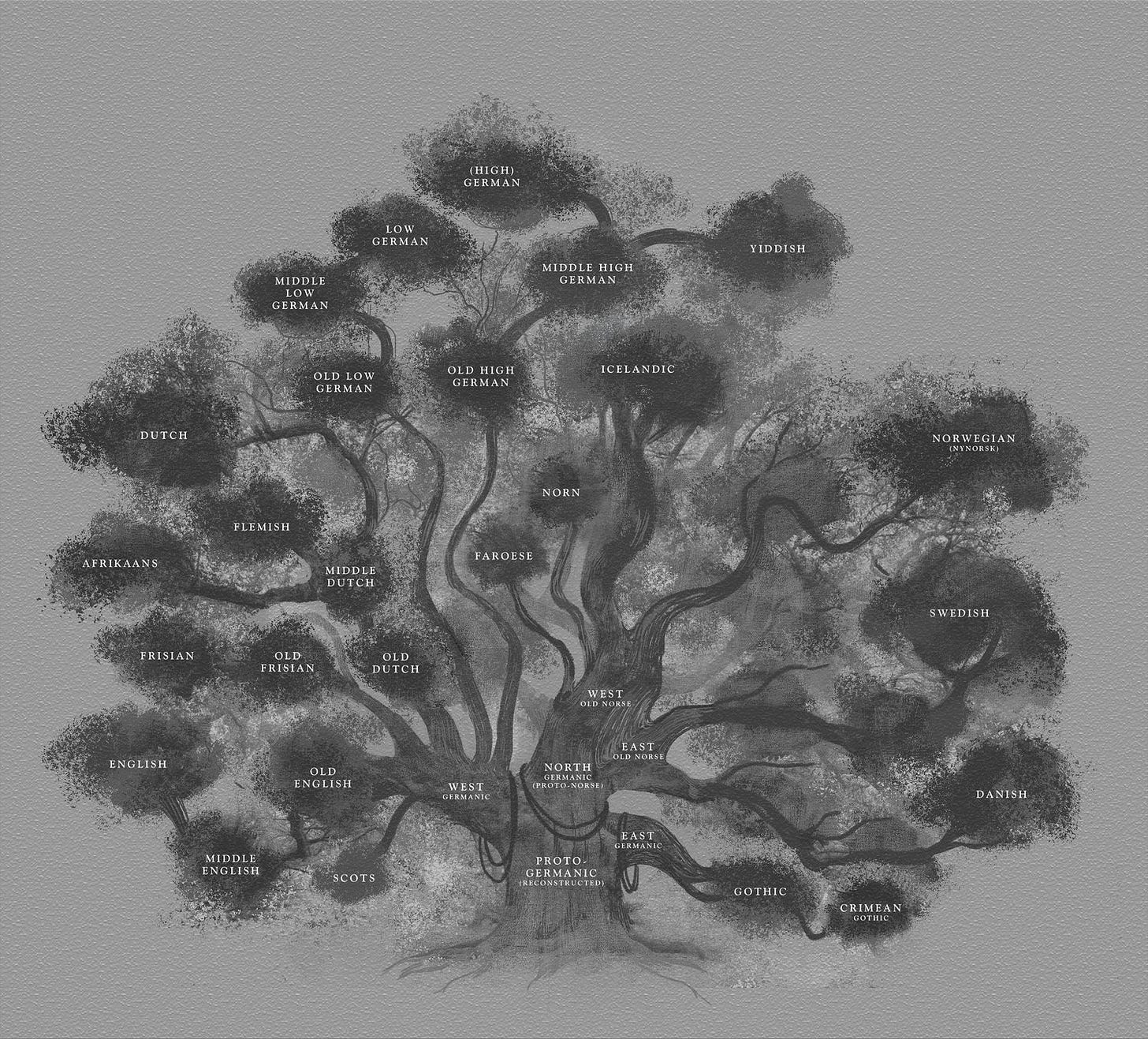

Germanic language, culture, and religion evolved as an offshoot of an earlier, stone-age, Indo-European tradition that arrived in southern Scandinavia with the Battle Axe (or Boat Axe) culture1 in the 3rd millennium BC. This culture absorbed some of the pre-existing populations in the area2, took on later influence from Central Europe, and was engaging in long distance trade by the Nordic Bronze Age34. We begin to call these people “Germanic” somewhere around the beginning of the Pre-Roman Iron Age5 in the 1st millennium BC with the emergence of Grimm’s Law:6 the first set of linguistic sound shifts that can be used to demarcate Germanic language as unique within the broader Indo-European language family.

Thus Germanic is an adjective that does not describe bloodlines, race, or ethnicity, but language. When we talk about Germanic religion and culture, we are talking about the practices of people who have been grouped together by shared language features that were inherited from a common ancestor language. In this case, the original collection of dialects sharing uniquely Germanic features is known together as Proto-Germanic.

Over the following centuries, Germanic people spread further into Central Europe, Scandinavia, and the islands of the North Sea and North Atlantic. With greater distance came greater variation in language, culture, and religion. Deities such as Wōðanaz, Tīwaz, and Þunraz in the once-common Proto-Germanic eventually became Óðinn, Týr, and Þórr in Scandinavia, Wōden, Tīw, and Þunor in England, and Wodan, Ziu, and Donar in central Germany (just to name a few), each with their own nuances and certainly some unique, regional stories.

In 13th century Iceland, over two-hundred years after Christianity had replaced paganism locally, a few stories reflecting the memory of one particular flavor of northwestern, Germanic paganism were finally written down. These stories are found within manuscripts that have been translated and compiled into two modern books, namely the Poetic Edda7 and the Prose Edda8, and comprise the bulk of what we now call “Norse mythology.”

The word Norse is a commonly-accepted English term referring to speakers of North-Germanic languages in the medieval period, thus making vikings and other medieval Scandinavians a historical subset of Germanic people. In terms of being religiously unique, ancient Norse pagans converted to Christianity later than all other Germanic groups, and it may be partially due to this fact that their society was able to record so much surviving mythological material.

Comparatively, there is scant Germanic mythological data to be found outside of Iceland and Scandinavia. But we do have hints at variations and similarities in the belief system. For example, the Second Merseburg Charm9 from 9th-century Germany mentions the characters Uuodan, Balder, and Friia (analogous with the Norse Odin, Baldr, and Frigg), alongside characters named Sunna (identical with the Norse goddess Sol10) Uolla (identical with the Norse goddess Fulla11), and Sinthgunt - a name that might be related to a Norse figure, but is not explicitly attested in the Norse corpus12. Another example is the Old Saxon Baptismal Vow13 from the 8th or 9th century which calls on a baptismal candidate to renounce the gods Uoden (Odin), Thunaer (Thor), and the mysterious Saxnote, who also appears in Anglo-Saxon royal genealogies, and whose name could be a reference to Freyr14, Tyr15, or potentially a Germanic adaptation of the Celtic god Nodens16. Even legendary Norse heroes such as Sigurðr and Vǫlundr respectively show up in the German and English record with names like Siegfried and Wēland.

Germanic mythology also retains similarities with its broader Indo-European cousins. To illustrate, one common motif found in many Indo-European traditions is that of the thundergod. This role is typically thought of as being filled by Thor in a Norse context, and in other contexts by the Slavic Perun, the Vedic Indra, the Greek Zeus, the Roman Jupiter, the Celtic Taranis, and others. Ancient people recognized these similarities when they encountered them, and that recognition paved the way for concepts such as interpretatio romana17 and interpretatio germanica18 wherein the Romans and the Germanic peoples each identified the deities of the other by the names of their own. Hence Tacitus wrote that “Mercury is the deity whom [the Germanic people] chiefly worship”19, and hence the Germanic names for certain weekdays were chosen in alignment with their Roman counterparts.

However, we, as a modern audience, would be unlikely to read a story involving Indra or Zeus and intuitively conclude that these figures are the exact same character as Thor, even if they do descend from common origins. There has been enough divergence that these characters feel unique to their contexts, even if we notice some similarities between them. On the other hand, divergence does not always imply this level of distinction. For instance, Spanish-speaking Catholics in South America would strongly disagree with English-speaking, North American Calvinists on many Christian doctrinal points, but despite the geographical distance between them, the differences in their practices and stories, and even their linguistically different names for Jesus, it is easy for us to recognize the Spanish, Catholic Jesucristo and the English, Calvinist Jesus Christ as the exact same character.

There would therefore seem to be some murky threshold of religious variation that, when crossed, two gods begin to be thought of as different characters bearing similarities versus the same character but with notable nuances. In the case of Þórr, Þunor, Donar, and other gods descended from the same Germanic root, it is a common, scholarly view that we ought to lean toward considering these figures as the same god, perhaps with some notable nuances, although it is admittedly hard to know exactly how close to the threshold they may sometimes lie.

The same is true of ancient Norse religion when compared to other members of the larger Germanic umbrella. As previously stated, far less pagan Germanic material has been preserved from outside Iceland and Scandinavia, yet what bits of information have been preserved point to a largely shared religious and mythological tradition among these linguistically related groups. Given that the ancient Germanic people were willing enough to interpret the Roman gods as being the same as their own by different names, it is at least safe to say that they would have seen through the variations that existed among themselves to the shared core beneath the surface.

Introductory information at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_Axe_culture

Price, Theron Douglas., Ancient Scandinavia: An Archaeological History from the First Humans to the Vikings, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 160

Bergerbrant, Sophie. (2007). “Bronze Age Identities: Costume, Conflict and Contact in Northern Europe 1600-1300 BC.”

Introductory information on the Nordic Bronze Age at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nordic_Bronze_Age

Introductory information at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archaeology_of_Northern_Europe#Pre-Roman_Iron_Age

Introductory information at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grimm%27s_law

Introductory information at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poetic_Edda

Introductory information at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prose_Edda

Introductory information at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merseburg_charms%23Second_Merseburg_Charm

Sól and Sunna are attested synonyms in the Norse corpus, as can be found in the Þulur. See https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=wordtextlp&i=308636

Although this word is spelled uolla in the manuscript, the scribe is employing a unique convention in which he spells the sound /f/ with the letter ⟨u⟩ when preceding vowels. Other examples include folon written “uolon”, and fuoz written “uuoz”. Thus this uolla ought to be read “folla”.

Simek, R., Dictionary of Northern Mythology, (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2007). p. 278

Introductory information at https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_Saxon_Baptismal_Vow

Simek, p. 276

Stallybrass, J.S., trans., Jacob Grimm: Teutonic Mythology, Volume I (Peter Smith Pub. Inc., 1976), ch. 9

Wagner, H. "Zur Etymologie von keltisch Nodons, Ir. Nuadu, Kymr. Nudd/Lludd" Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie, vol. 41, no. 1, 1986, pp. 180-182.

Introductory information at https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interpretatio_graeca

Introductory information at https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interpretatio_germanica

Church, A.J. and Brodribb, W.J. trans., Publius Cornelius Tacitus: Germania, s 9.

Concise and thoughtful, thank you.