In the poem Grímnismál, Odin provides us with an intriguing little piece of information that is not expanded upon anywhere else in Norse mythological source material. It is reiterated by Snorri in the Prose Edda, but he provides no substantive information outside of what we find in that single, Eddic stanza.

Here it is, stanza 14:

Fólkvangr er inn níundi, en þar Freyja ræðr | sessa kostum í sal; | hálfan val hon kýss hverjan dag, | en hálfan Óðinn á.

Folkvang is the ninth [location among the gods], and there Freyja governs choice of seats in the hall; half the slain she chooses every day, and half Odin owns.

Traditionally, this stanza has been taken to mean that half the warriors who die in battle are relegated to Freyja’s dwelling, Folkvang, while the other half find their way into Valhalla. But this information is obscure. In order to have any hope of properly interpreting it, we need to have a correct interpretation of the phrase “choose the slain,” which is not entirely clear without additional context. Fortunately, this idea is repeated quite frequently in our sources (especially with regard to the actions of valkyries) and plenty of context does exist surrounding those other references.

As it turns out, to “choose the slain” does not mean to make a selection from among those who have already died. What it does mean is to choose who will die. Consider the following passages:

Gylfaginning 36:

Þessar heita valkyrjur. Þær sendir Óðinn til hverrar orrustu. Þær kjósa feigð á menn ok ráða sigri. Guðr ok Róta ok norn in yngsta, er Skuld heitir, ríða jafnan at kjósa val ok ráða vígum.

These are called valkyries. Odin sends them to every battle. They choose when death comes for men1 and govern victory. Gud and Rota and the youngest norn, who is called Skuld, always ride to choose the slain and govern the killings.

Atlamál in grǿnlenzku 28:

Konur hugðak dauðar koma í nótt hingat; | værit vart búnar, vildi þik kjósa, | byði þér brálliga til bekkja sinna; | ek kveð aflima orðnar þér dísir!

I thought dead women came here in the night; they were not poorly clothed, they wanted to choose you, bid you quickly to their benches (i.e. bring you into the realm of the dead); I say that the dísir (probably ancestral, guardian spirits) have become powerless [to help] you.

Sigdrífumál prose interjection after stanza 4:

Hon nefndisk Sigrdrífa, ok var valkyrja. Hon sagði at tveir konungar bǫrðusk. Hét annarr Hjálmgunnarr. Hann var þá gamall ok inn mesti hermaðr, ok hafði Óðinn honum sigri heitit. En annarr hét Agnarr, Hauðu bróðir, er vætr engi vildi þiggja. Sigrdrífa feldi Hjálmgunnar í orrostunni. En Óðinn stakk hana svefnþorni í hefnd þess ok kvað hana aldri skyldu síðan sigr vega í orrostu ok kvað hana giptask skyldu.

She was named Sigrdrifa, and was a valkyrie. She said that two kings fought each other. One was called Hjalmgunnar. He was then old and the greatest warrior, and Odin had promised him victory. The other was called Agnar, Hauda’s brother, whom no creature wanted to receive. Sigrdrifa felled Hjalmgunnar in the battle. And Odin stuck her with a sleep-thorn in revenge for this and said that she should never thereafter win victory in battle and said that she should be married.

Vafþrúðnismál 41:

Vafþrúðnir kvað: | ‘Allir einherjar Óðins túnum í | hǫggvask hverjan dag; | val þeir kjósa ok ríða vígi frá, | sitja meirr um sáttir saman.’

Vafthrudnir said: “All the Einherjar fight each other in Odin’s enclosed fields every day; they choose the slain (i.e., kill each other) and ride from the battle, to sit more together in accord.”

Grímnismál 8:

Glaðsheimr heitir inn fimmti, þars in gullbjarta | Valhǫll víð of þrumir; | en þar Hroptr kýss hverjan dag | vápndauða vera.

The fifth [location among the gods] is called Gladsheim, there the gold-bright Valhalla stands widely; and there Hropt (Odin) chooses every day the weapon-dead men (i.e., chooses who will be killed by weapons).

Thus the role of a valkyrie is to govern victory in battle by choosing who will be killed (i.e., choosing the slain). This is not a matter of looking at two dead warriors and selecting one of them for Valhalla; it’s a matter of selecting a living warrior and bringing about his death so that he can then be received into Valhalla. This makes a lot of sense in light of what we are told in Gylfaginning 20 and 38, that “all those” who have ever fallen in battle since the world began have arrived in Valhalla as Odin’s adopted sons, not just some of them.

This, of course, leads into all sorts of questions about how intertwined valkyries are with fate. In fact, there is a concept in scholarship, often termed the “dís-valkyrja-norn complex”2, recognizing the interesting overlap between these three groups of women. However, that conversation is beyond the scope of this post. Suffice it to say that valkyries appear to be part of a complex of supernatural women in Norse mythology who are tied to fate in some way and make decisions about who lives and who dies in a battle. We have no reason to believe that they choose from among already-slain warriors to determine which are worthy of Valhalla.

Is Freyja a valkyrie?

Maybe. Freyja is certainly one of the many supernatural women in our sources linked to fate, war, and death. She participates in choosing the slain (Vafþrúðnismál 41), which Snorri says happens “whenever she rides into battle” (Gylfaginning 24). She serves ale in Valhalla (Skáldskaparmál 17) as other valkyries named in Vǫluspá do (Grímnismál 36). She has a bird-skin garment that allows her to fly (Þrymskviða 3-5, Skáldskaparmál, 56) which is reminiscent of the valkyries’ “swan garments” mentioned in Vǫlundarkviða (prose intro, st. 2). There’s a lot about her that looks particularly valkyrie-esque. However, even though she seems to embody all of the common attributes of a valkyrie, she is never explicitly called a valkyrie in the sources (much less “queen of the valkyries” or any such thing like that).

Do the valkyries work for Odin?

Snorri mentions in Gylfaginning 36 (quoted above) that Odin sends the valkyries into battle, however there’s an interesting conversation to be had around what level of control he really has over them. In that same passage, Snorri tells us that valkyries dole out death, choose the slain, and govern the killings, although Grímnismál 8 (also quoted above) contends that Odin himself “chooses the slain”.

We might assume that the valkyries ensure the deaths of those whom Odin has selected, and to some degree this may be true. However, fascinatingly, the above passage from Sigrdrífumál provides an attestation of a valkyrie bringing down a king to whom Odin had previously promised victory, in defiance of his desires and much to his apparent chagrin. It is not made explicit what her motivation for this might have been. However, it is interesting to note that stanza 1 of Vǫlundarkviða describes the valkyries as beings who “fulfill fate”:

Meyjar flugu sunnan | Myrkvið í gøgnum, | alvitr ungar, | ørlǫg drýgja; | þær á sævar strǫnd | settusk at hvílask, | drósir suðrœnar | dýrt lín spunnu.

Maidens flew from the south across Murkwood, young foreign beings3, to fulfill fate; they were set at rest upon the lakeshore, the southern girls spun valuable linen.

Additionally, we learn from Vǫluspá 20 (supplemented by various other references4) that fate is determined by the women called norns:

Þaðan koma meyjar, | margs vitandi, | þrjár, ór þeim sæ | er und þolli stendr; | Urð hétu eina, | aðra Verðandi — | skáru á skíði — | Skuld ina þriðju; | þær lǫg lǫgðu, | þær líf kuru | alda bǫrnum, | ørlǫg seggja.

From there come maidens, much knowing, three from out of that sea which stands under the tree: One is called Urd, another Verdandi — they scored upon a piece of wood — Skuld the third; they laid down laws, they chose lives for the children of ages, the fates of men.

The gods, interestingly, are not in full control of fate. Rather, they are subject to their own fates as are all other beings. Baldr’s death, for instance, is called “fate” (ørlǫg) in Vǫluspá 31, and of course the entire concept of ragnarǫk (lit., “fated course of the Powers”) is discussed at length in various sources.

Thus we have fate being shaped by norns, independent of the gods, and fulfilled by valkyries. One of those norns even serves as a valkyrie herself. We also have an attested instance of one valkyrie defying Odin’s wishes. Even though valkyries appear to collect dead warriors on Odin’s behalf, we are still left to assume that Odin may not always get everything he wants when it comes to those who die in battle. If we are looking for a simple, creative suggestion as to why Sigrdrifa might have killed Hjalmgunnar instead of Agnar, perhaps it is no more complicated than the fact that her job was, above all else, to fulfill fate, and perhaps Odin’s desire in this case was at odds with what the norns had decreed.

The most intriguing part of this question, to me, is figuring out how we are intended to reconcile the fact that fate (and most importantly a person’s time of death) is decreed by norns when, at the same time, Odin also “chooses the slain”, functions as a psychopomp, and is essentially a god of dead warriors.

What does all this have to do with Folkvang?

All of this is important context needed for interpreting Grímnismál 14 which, to reiterate, is a single stanza serving as the only source for everything we know about Folkvang. So let’s turn to the Prose Edda to try and figure out how Snorri interprets what happens to those who fall in battle. On the one hand, he gives us Gylfaginning 24:

Hon á þann bæ á himni, er Fólkvangr heitir. Ok hvar sem hon ríðr til vígs, þá á hon hálfan val, en hálfan Óðinn […]

[Freyja] owns that dwelling in heaven which is called Folkvang. And wherever she rides to battle, then she owns half the slain, and half Odin [owns].

On the other hand, he gives us Gylfaginning 20 and 38:

Hann heitir ok Valfǫðr, því at hans óskasynir eru allir þeir, er í val falla. […] Þat segir þú, at allir þeir menn, er í orrustu hafa fallit frá upphafi heims eru nú komnir til Óðins í Valhǫll.

[Odin] is also called Slain-father, because all those who fall as slain-dead are his adopted sons. […] You say this, that all those men, who have fallen in armed-combat since the world’s beginning are now come to Odin in Valhalla.

So how is it that Freyja can get half the slain while, at the same time, “all” of them belong to Odin?

Because choosing the slain means choosing who dies, and because valkyries are beings who both work on Odin’s behalf but also to fulfill fate, it seems to me that the simplest explanation for this half-and-half split is that Freyja is in charge of dealing out half the deaths and Odin is in charge of dealing out the others. If Freyja represents the interests of the dís-valkyrja-norn complex in opposition to Odin, then Grímnismál 14 (the Folkvang stanza) is almost certainly describing a division of control over who dies, not a division of dead warriors into separate afterlife realms.

Scholars are interestingly torn on the idea of Folkvang. Simek’s opinion5, for instance, is that Odin and Freyja are both choosing warriors for Valhalla. Lindow, on the other hand, views Folkvang as an “alternative to Valhöll”, though still a place for Einherjar awaiting Ragnarok6. I personally lean more toward Simek’s opinion in this case because I see it as providing the most seamless reconciliation among all the points we’ve seen in the sources so far. It also works well alongside the notion of ancient rituals wherein the souls of the dead (even entire armies!) could be dedicated specifically to Odin7. Such rituals seem less meaningful in light of a 50/50 chance that Freyja might hijack a person’s intended afterlife destination after the death occurs.

Is Folkvang the same thing as Valhalla?

Not exactly. As opposed to Valhalla, Folkvang is not a hall. The word itself either means “people-plain” or “army-plain”8 and, like some of the other places named in Grímnismál’s list of locations among the gods (e.g., Gladsheim and Breidablik), it has a hall standing somewhere within it.

“The hall” wherein Freyja governs choice of seats in Folkvang is not specifically named in the Poetic Edda. It is therefore not impossible that the hall is meant to be Valhalla and the fólk-vangr (people/army-plain) in question is perhaps the surrounding area wherein the Einherjar “fight each other in Odin’s enclosed fields every day” (Vafþrúðnismál 41).

If so, we might want to reconcile this against the fact that Snorri gives the name of Freyja’s hall as Sessrúmnir (not Valhǫll) in Gylfaginning 24.

Salr hennar Sessrúmnir, hann er mikill ok fagr.

[Freyja’s] hall Sessrumnir, it is large and beautiful.

This name does not occur in any surviving pagan-era poetry and we have absolutely no idea where Snorri got it from, not being a pagan himself. It’s hard to judge Snorri’s interpretation accurately since he provides no source for his claim and some of his unsourced claims are dubious9. It’s worth noting, however, that the word sessrúmnir means, literally, “seat-roomer”. If we had no extra information, we may be tempted to guess that Sessrumnir was originally intended as a synonym for Valhalla, it being a great room containing thousands of seats (Grímnismál 23).

However, we do have some extra information on this word. In the Nafnaþúlur (often labeled Skáldskaparmál 75), Sessrumnir is also given as the name of a ship:

Nú mun ek skýra | of skipa heiti. | Ǫrk, árakló, | askr, sessrúmnir, | skeið, skúta, skip | ok skíðblaðnir, | nór, naglfari, | nǫkkvi, snekkja.

Now I will expound upon ship names. Ark, Oar-Claw, Ash, Sessrumnir (Seat-Roomer), Sheath, Scout, Ship and Skidbladnir (Plank-Blader), Nave10, Naglfari (Nail-farer), Rowboat, Smack.

Assuming that Sessrumnir is supposed to be a name for a ship, we now have a simpler and far more reasonable lens through which to interpret the meaning of the phrase “seat-roomer”. As it turns out, the Old Norse language conventionally describes ships in terms of their seating capacity, with the word sessa describing a seat11 and the word rúm describing a row of two seats that operate a pair of oars (a “room” divided into two half-rooms)12. Consider the following snippets provided by Cleasby/Vigfússon13:

Ásbjörn átti langskip, þat var S. tvítug-sessa (Asbjorn had a longship that was a smack of twenty seats)

hann lét reisa langskip mikit, þat var S., skipit var þrítugt at rúma-tali (He had built a large longship that was a smack, the ship was numbered at thirty oar-rooms.)

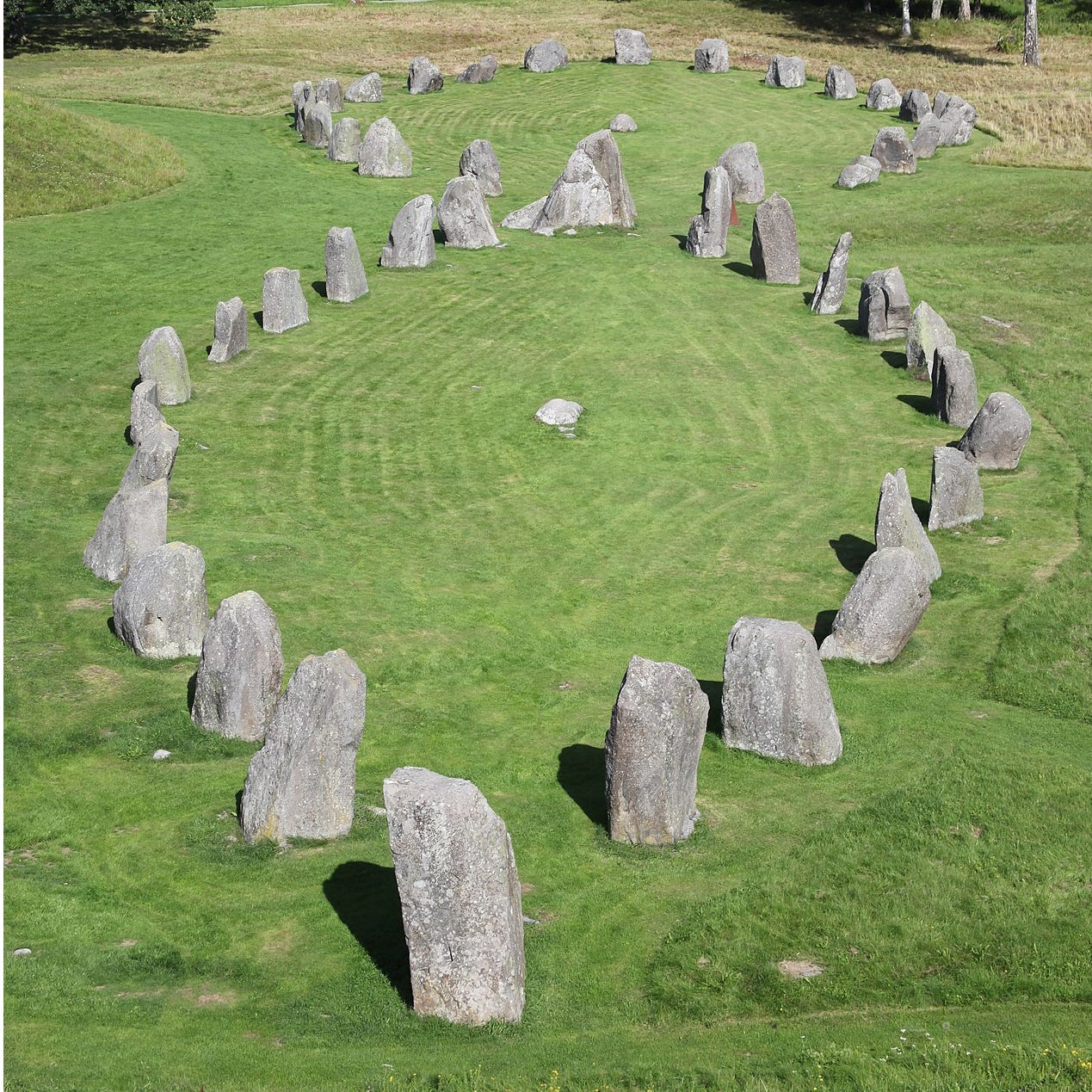

Simek suggests14 that one of these two concepts, either the hall or the ship, might be a misunderstanding on Snorri’s part. Hopkins and Haukur, on the other hand, suggest15 that a connection between Sessrumnir and Folkvang can be seen in the existence of stone ship monuments which tend to lie in open fields throughout Scandinavia. In that light, as well as in light of the tradition of burial mounds resembling ships, it’s possible that Sessrumnir as a ship-burial ritually represents Sessrumnir as an afterlife location. This, of course, does not preclude a connection to Valhalla, but could possibly even tie these concepts more closely together. Suppose, for instance, that a king is buried in a Sessrumnir (a ship-shaped grave) in the middle of a Folkvang (a burial field) and thus finds his way into Valhalla, all after having been chosen for death by Odin or Freyja.

So what’s the verdict?

Unfortunately, there is essentially nothing else ever said about Folkvang in our sources other than the fact that Snorri places it “in heaven”, and we have already seen how his desire to position mythological locations in heaven sometimes causes his ideas to deviate from pagan-era material16.

In light of the scant information we have, a solid interpretation of the Valhalla-Folkvang problem must work well in light of the following facts:

that Freyja and Odin each choose half the slain each day;

that Freyja governs choice of seats in the hall standing at Folkvang;

that deaths can be dedicated to Odin (assumedly without interference from Freyja);

and that Odin is the owner of all those who have ever died in battle.

To me, the one interpretation that seems to fit all of these ideas is the one in which Odin and Freyja are not dividing the slain into separate afterlife locations, but are instead sharing the job of choosing which warriors will die. These warriors are then shepherded to Valhalla (perhaps by means of a ship, either literal17 or ritualistic) where Freyja governs choice of seats and serves ale. This interpretation adheres to the consistent meaning of the phrase “choose the slain” in source material, whereas the other interpretation (wherein dead warriors are selected for different locations) seems to misunderstand it.

To bolster this idea a bit more, it’s worth noting that we are suspiciously lacking any accounts of anyone actually going to Folkvang instead of Valhalla in our sources. If the division between Freyja and Odin is as simple as a compromise on selecting which warriors die, with all those warriors ending up in the same place, our lack of these accounts ceases to be strange and becomes expected.

If Freyja represents the interests of the valkyries, her involvement can be seen in the various attestations of valkyries bringing down warriors, as well as Snorri’s claim that she personally rides to battle to choose the slain. We also have attestations of Odin personally involving himself in the battle-deaths of various individuals, for instance Sigmund in Vǫlsunga saga and Harald Wartooth in Gesta Danorum. Warriors such as these die on a literal fólk-vangr, they are often buried in what could easily be called a fólk-vangr, and spend their afterlife days fighting on another literal fólk-vangr before heading back into Valhalla to feast in the evenings.

All this information seems to draw a fairly obvious connection between Folkvang and Valhalla, and I see no reason to assume they represent alternative afterlives. In fact, another Indo-European afterlife location spoken of among the ancient Greeks bears similarities all around. Elysium (also known as the Elysian Fields or Plains) is a place reserved for relatives of the gods as well as kings, heroes, and individuals personally chosen by the gods18, very much like Valhalla and its surrounding battlefields.

Further Evidence in Egils Saga

There is a relatively famous passage in Egils saga Skallagrímssonar19 occurring after Egil’s son Bodvar drowns in a boating accident. As a result of the death, Egil becomes depressed and loses his will to live. Upon hearing about this, his daughter Thorgerd comes to visit and, when asked whether or not she has already had supper, she replies:

Engan hefi ek náttverð haft, ok engan mun ek fyrr en at Freyju. Kann ek mér eigi betri ráð en faðir minn. Vil ek ekki lifa eftir föður minn ok bróður.

I have not had supper, nor will I until (I do) at Freyja’s. I can not do better for myself than my father. I do not want to live after (i.e. outlive) my father and brother.

After making this declaration, Thorgerd joins Egil and tricks him into believing the two of them will be poisoning themselves together. When they are unharmed by the fake poison, Thorgerd suggests that, since their plan has failed, Egil should compose a poem in memory of his son. Afterwards, if he still wants to die, she will die with him then. Composing the famous poem Sonatorrek ultimately allows Egil to process his grief and he regains his will to live.

Whereas Thorgerd mentions joining Freyja (by means of dying alongside her father by self-poisoning), she makes no mention of Folkvang. This method of death, we ought to note, does not technically involve becoming chosen slain, however Egil’s poem does contain two particular stanzas that are likely relevant here:

18: Erumka þekkt | þjóða sinni, | þótt sér hverr | sátt of haldi. | Burr Bileygs20 | í bæ kominn, | kvánar sonr, | kynnis leita.

18: People are not pleasing to me, though everyone acts agreeably. [My] son has come in to Bileyg’s [= Odin’s] estate, [my] wife’s son, to visit.

[…]

25: Nú erum torvelt, | Tveggja bága | njǫrva nipt | á nesi stendr, | skalk þó glaðr | góðum vilja | ok ó-hryggr | heljar bíða.

25: Now I am unwell, the kinswoman of Tveggi’s [= Odin’s] strife (Hel) stands upon the narrow headland, though I shall await Hel gladly, in good will, and un-grieved.

Egil explains here that he expects to be received by Hel, though he discusses his relationship with Odin repeatedly throughout the poem and notes that his son, who did not die in battle, has ventured to Odin’s estate. It seems clear that Egil’s family is deeply associated with Odin worship, so it is a little strange that Egil doesn’t expect to go to Valhalla himself, though his reasoning may be revealed in stanzas 22-23:

Áttak gótt | við geirs dróttin, | gerðumk tryggr | at trúa hǫ́num, | áðr vinan | vagna rúni, | sigrhǫfundr, | of sleit við mik. | Blœtka því | bróður Vílis, | goðjaðar, | at gjarn séak, | þó hefr Míms vinr | mér of fengnar | bǫlva bœtr, | es et betra telk.

I had it good with the Lord of Spears (Odin), I made myself faithful at believing in him, before the Chariot-Friend, the Victory-Author (Odin), broke off friendship with me. I do not sacrifice therefore to Vili’s brother, Highest-God (Odin), because I am eager to, although Mim’s friend (Odin) has fetched me remedies for bales, when I count the better (i.e., when I look on the bright side).

In a previous post21 I discussed the idea that initiation into the cult of Odin seems to have been sufficient to grant certain people entry into Valhalla, and it may be that very principle at play here in the case of Egil’s son. It follows, then, that Egil should have expected to go to Valhalla as well, but Egil now believes Odin has forsaken him and he has either chosen to discontinue ritual worship or to continue it begrudgingly (the phrasing is notoriously hard to parse22). Either way, his relationship with Odin has been frustrated, he no longer sees himself as Odin’s “friend”, and this may be why he expects to be met by Hel upon his death. Alternatively, it is not impossible that Hel stands in here as a metaphor for death and burial, in which case it would not necessarily mean Egil no longer expects entry into Valhalla. Consider, for example, the hero Sigurd’s assertion in Fáfnismál 10 that:

[…] einu sinni skal alda hverr fara til Heljar heðan.

At one time shall every man travel from here to Hel.

Perhaps this is meant to include those ultimately destined for Valhalla.

Given the tight connection between Egil’s family and Odin, it is interesting that Thorgerd (Egil’s daughter) describes her expected afterlife as one in which she joins Freyja. If it is true that Folkvang is not inherently disconnected to Valhalla, then perhaps this is a Norse woman’s way of describing her own expected role in Valhalla alongside her other Odin-cult-initiated family members (which likely includes her husband Olaf, as he is a nobleman as well).

It is unlikely that the average noblewoman following her husband into the afterlife would expect to join the ranks of the Einherjar herself in Valhalla. In that case, perhaps it is not too much of a stretch to imagine that such a woman joins Freyja, perhaps finding a place among the ranks of the dísir, who seem to have functioned somewhat like female, ancestral, guardian spirits. In any case, I am of the opinion that this episode in Egils saga serves to strengthen the connection between a Freyja-centric afterlife and an Odin-centric afterlife, given that all the males of Egil’s family are associated with Odin while his daughter associates herself with Freyja.

Of course, the simplest interpretation is the idea that, when you die, you may just go wherever it is you believe you are going to go for whatever reason you have that makes you believe you’ll go there. I don’t believe that Grímnismál is trying to distinguish Folkvang as an afterlife separate from Valhalla, but there are many halls among the gods and contradictions in the sources abound. Asgard is just a city, after all, and we have no reason to assume a person received into any given hall would be imprisoned in that building, unable to experience any other location in the same city of the gods.

Epilogue (or, Why is Grímnismál so ambiguous?)

It probably wouldn’t have been ambiguous to its intended audience, who would have understood it in the context of their own well-understood belief system. Unfortunately we, in modern times, are at a bit of a loss there.

One other point that could potentially play a role in the confusion between Valhalla, Sessrumnir, Folkvang, and the 50/50 compromise between Odin and Freyja is the hypothesis that, at some point in the past, Freyja and Frigg (Odin’s wife) could have been a single figure who later split into two23. That debate is beyond the scope of this post but, if it is correct (or if something like it is correct), it could mean that, in the more distant past, joining Frigg-Freyja in the afterlife might have been more obviously equated with joining Odin since the two would have been married and shared joint interests.

This idea (or even its opposite, an in-progress merger between Frigg and Freyja) could potentially help explain why men and women in the same family would have respectively associated themselves with Odin and Freyja as we see in Egils saga, and why Odin would need to establish any kind of compromise with Freyja in the first place or why she would hold such a prominent role in his hall. Simek believes that Folkvang “is surely not much older than Grímnismál itself”24 and, while Simek is sort of notorious for making definitive statements backed by very little data, it is entirely plausible that Grímnismál illustrates a notion of the afterlife that was unique to the 900s, or one that was in flux at the time.

The phrase “they choose when death comes for men” hinges on the Old Norse word feigð, meaning “feyness” (i.e., a state of impending death) according to the Cleasby & Vigfusson Dictionary of Old Icelandic.

Cleasby, Richard, and Guðbrandur Vigfússon. “Feigð.” Cleasby & Vigfusson - Old Norse Dictionary, cleasby-vigfusson-dictionary.vercel.app/word/feigd. Accessed 6 Mar. 2024.

Simek, R., Dictionary of Northern Mythology, (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2007). pp. 206-207.

The word alvitr (foreign being) seems to be a known ancient description of a valkyrie. It occurs again in Hegakviða Hundingsbana II 20 with the same meaning.

For instance, Helgakviða Hundingsbana I 2-3, Hegakviða Hundingsbana II 20, Fáfnismál 11 and 44, Sigurðarkviða in skamma 7, Hamðismál 29-30, and Gylfaginning 16.

Simek, R., Dictionary of Northern Mythology, (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2007). p. 87

Lindow, J., Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 118

See my post “The Norse Afterlife Part I: How to Get to Valhalla”.

The O.N. word fólk could be used in the same sense as English “folk”, but was also commonly used to refer to a host of soldiers. Consider Vǫluspá 24: Fleygði Óðinn ok í fólk um skaut — þat var enn fólkvíg fyrst í heimi; “Odin let fly (his spear) and shot into the (opposing) army — that was the first tribe-war in the world;”.

For instance, Snorri’s claim that Thor must not be without a pair of iron gloves while using his hammer is almost certainly incorrect. See my post “The Germanic Thunderweapon Part I: Mjollnir’s True Power”.

Assumes O.N. nór is related to Latin navis. In any case, it is just another type of ship.

Cleasby, Richard, and Guðbrandur Vigfússon. “Snekkja.” Cleasby & Vigfusson - Old Norse Dictionary, cleasby-vigfusson-dictionary.vercel.app/word/snekkja. Accessed 6 Mar. 2024.

Simek, p. 280.

Hopkins, Joseph S. and Haukur Þorgeirsson (2012). "The Ship in the Field". RMN Newsletter 3, 2011:14-18. University of Helsinki.

The classic example can be seen in Snorri’s description of Yggdrasil’s roots (Gylfaginning 15) contrasted against the description given in Grímnismál 31. Snorri chooses to position Urd’s Well in heaven which results in a description of Yggdrasil’s third root first extending toward Niflheim, and then making a strange, right-angled turn up into the sky in order to reach Urd’s Well, completely uncharacteristic of a tree root. By contrast, Grímnismál has each root simply “extending outward in three directions” toward the realms of Hel, the frost-thurses, and humankind.

Note also that in Vǫlsunga saga, Sinfjotli is taken to Valhalla on a boat ferried by Odin.

Sacks, David (1997). A Dictionary of the Ancient Greek World. Oxford University Press US. pp. 8, 9.

“Egils saga Skalla-Grímssonar.” Heimskringla.no, https://heimskringla.no/wiki/Egils_saga_Skalla-Gr%C3%ADmssonar. Accessed 6 Mar. 2024.

Following Nordal’s reading, 1933.

The phrasing in question is Blœtka því | bróður Vílis, | goðjaðar, | at gjarn séak. Word-for-word this means literally, “I do not sacrifice therefore to Vili’s brother, Highest-god, because I see eager.” To “see eager” is likely another way of expressing a state of being (i.e., to be continually eager). But it is difficult to determine whether Egil is saying he no longer sacrifices at all on account of his eager state (perhaps referring to a longing for his dead son?), or that he continues to perform sacrifices thought not because he is enthusiastic to do so. My translation here leans toward the latter interpretation. In either case, his relationship to Odin has been frustrated by the event.

See my post “Are Frigg and Freyja the same person?”

Simek, 2007. p. 87.

Thanks very much again! This was another worthy instalment.