Are Frigg and Freyja the Same Person?

Gaining some perspective on the Frigg/Freyja Common Origin Hypothesis

Prior to November, 2022, most newcomers to Norse mythology were entirely unaware of a theory in the academic community that the Norse mythological goddesses Frigg and Freyja might have been a single character somewhere in the distant past. Only a few months later, pop culture had all but canonized the idea that these two characters are one and the same. Why the change? Because this is how Santa Monica Studio chose to portray them in the smash-hit video game “God of War: Ragnarok”, released on November 9, 2022.

Getting right to it, Frigg and Freyja are not the same person in Norse mythology.

This is a testament to how much power an entertainment studio can have to affect broad changes in the collective mindset about a topic. Even when such a studio may choose to inform its content with copious research, it is never obligated to adhere to that research when presenting a final product.

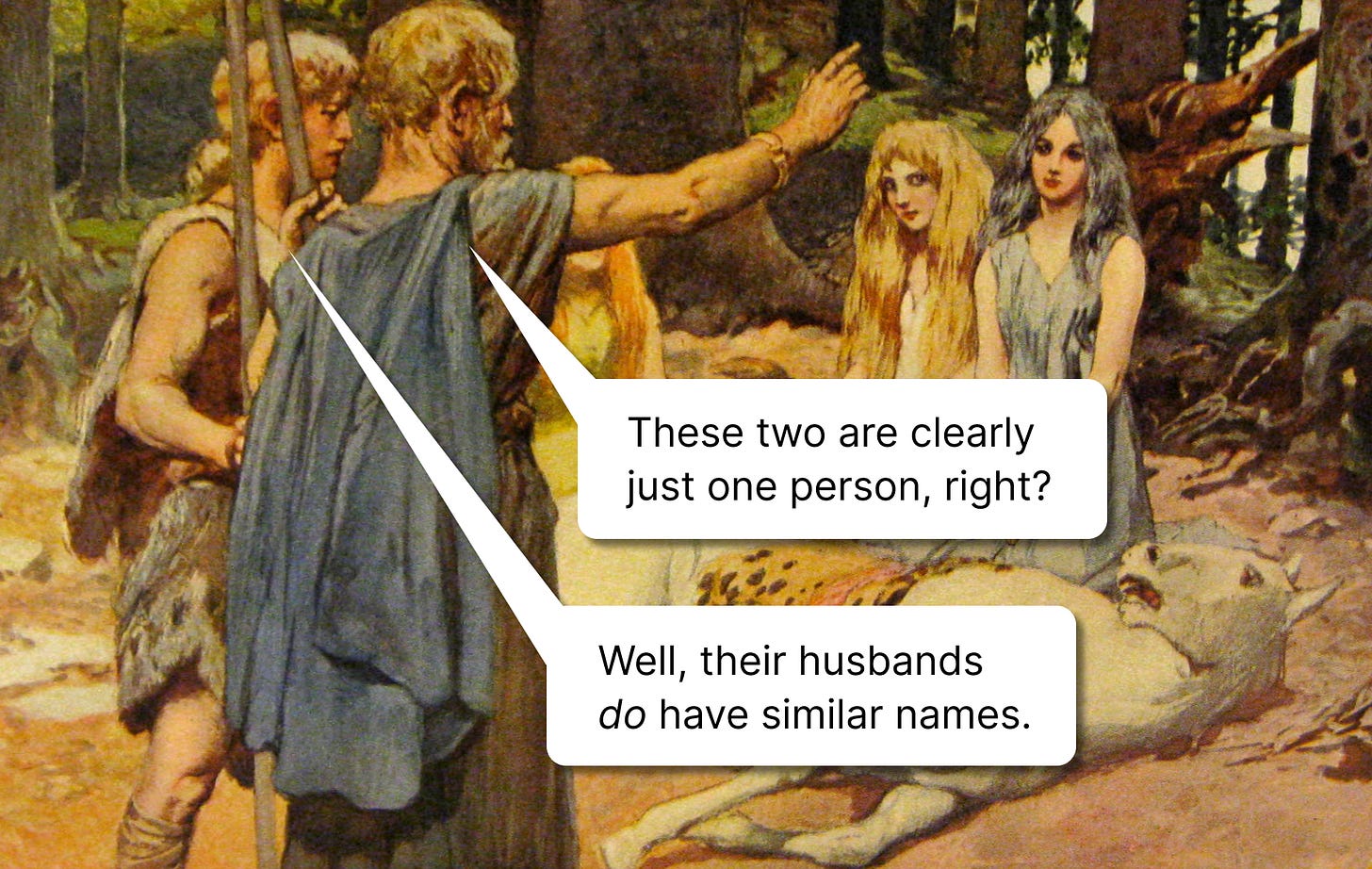

In the past when I have mentioned in conversation that Frigg and Freyja are not the same person, the reply I’ve gotten has sometimes resembled the following:

“But can you really prove Frigg and Freyja are not the same? I mean, have you ever seen them in the same room at the same time?”

Yes.

The poem “Lokasenna” tells the story of a feast attended by many of the gods wherein Loki murders a servant and then proceeds to insult all of the other guests. As it exists in surviving sources, the poem begins with a prose introduction containing a list of all characters in attendance:

To that feast came Óðinn and Frigg, his wife. Þórr did not come, because he was on the east-way. Sif, Þórr’s wife, was there, and Bragi and Iðunn, his wife. Týr was there. He was one-handed: Fenrisúlfr bit off his hand when he was bound. Njǫrðr was there, as was his wife, Skaði, Freyr and Freyja, [and] Víðarr, Óðinn’s son. Loki was there, and Freyr’s servants, Byggvir and Beyla. Many of the Æsir and elves were there.1

The poem also contains dialogue from both women. Frigg exchanges insults with Loki in stanzas 25-28, and then passes the torch to Freyja in stanza 29, wherein Freyja even refers back to Frigg in the third person:

Freyja said: ‘You’re mad, Loki, when you speak your hideous, loathsome words; I think that Frigg knows all fates though she doesn’t say them herself!’2

Due to instances of V/R alliteration3, the composition of this poem can be pretty confidently dated to the 900s A.D. or earlier, which is prior to the Icelandic conversion to Christianity. In other words, this poem is a scientifically supported reflection of Viking-Age, pagan-era belief that very clearly depicts Frigg and Freyja as two separate characters.

Side note: Though the Encyclopedia Britannica4 strangely parrots an old idea by Franz Rolf Schröder that “Lokasenna” is a 1200s adaptation of Lucian’s “Assembly of the Gods,” this idea is not accepted by the academic community at large and the article where it originates has even been described by Joseph Harris5 as “one of the most learned failed attempts to establish a date and source for an eddic poem”.

The Prose Edda also treats Frigg and Freyja as two separate characters in no uncertain terms. Freyja is named as a Vanir goddess whereas Frigg is not6, in paragraphs that fall one right after the other, and there are plenty of statements such as the following from Gylfaginning 35:

Then spoke Gangleri: "Who are the Asyniur?" High said: “The highest is Frigg. She has a dwelling called Fensalir and it is very splendid. […] Freyia is highest in rank next to Frigg.”7

The cherry on top, of course, is that there are no sources competing with this view– no sources indicating that Frigg and Freyja should be treated as two different names for the same character.

But if Frigg and Freyja are not the same, why is there a theory that they might be?

To be clear, there is no theory that Frigg and Freyja are the same person in our surviving corpus of myths. The theory (normally called The Frigg/Freyja Common Origin Hypothesis) is that these two characters might be descended from a common origin in earlier Germanic mythology from hundreds of years before the Norse period began. Here’s some of the circumstantial evidence that has led a few scholars to make this guess:

Freyja seems to have no name.

As it turns out, the Old Norse words Freyr and Freyja are titles, respectively meaning “Lord” and “Lady”. In the case of Freyr, our sources provide a name that accompanies the title: Yngvi, giving us the Old Norse compound Yngvi-Freyr8 (Lord Yngvi). In fact, whereas Germanic Scandinavians tended toward shortening this name to Freyr over time, other Germanic groups leaned more into calling him “Ing”. For instance, the Old English poem “Beowulf” refers to Danish King Hrothgar as eodor Ingwina9, meaning “prince of the friends of Ing”. Because Freyr has a name accompanying his title, we might expect to find a name accompanying the title Freyja as well, yet our Norse sources contain no such name. So the question is why not? Might her name have been Frigg-Freyja (“Lady Frigg”), once upon a time?

Playing Devil’s Advocate

Just because our surviving sources don’t give us an obvious name to accompany the title Freyja, doesn’t mean it must have been Frigg in earlier times. In fact, if we assume this name would have adhered to constantly repeated themes among divine name-pairs (e.g., Vili and Vé, Magni and Móði, Njǫrðr and Njǫrun, etc), we should expect a name that alliterates with Yngvi, which Frigg does not.

Freyja doesn’t exist outside of Scandinavia.

Norse mythology as it survives today is just one northwestern flavor of broader Germanic mythology.10 It’s part of a religious family that shares common origins with traditions such as ancient Anglo-Saxon mythology and ancient German mythology. In that light, just as Odin has counterparts in other Germanic traditions (Wōden in Old English and Wodan in Old High German, for instance), Frigg has counterparts as well (Frīg and Friia, respectively). However, we don’t have any references to a counterpart for Freyja outside of the Norse tradition. Does this mean she is unique to Norse mythology? And if so, is that because she split off from Frigg in Scandinavia at some point in the past?

Playing Devil’s Advocate

Germanic mythological sources outside of the Norse tradition are scant and incomplete. Even though the information we have doesn’t mention a counterpart for Freyja, this doesn’t mean she didn’t exist. Additionally, Germanic deities often go by multiple names and there are goddesses mentioned in material outside of Scandinavia that are likewise not mentioned in the Norse sources. For instance, Ēostre is an Anglo-Saxon goddess (*Ôstara in Old High German) who appears heavily associated with spring and fertility11. Her name even begins with a vowel, which would allow it to alliterate with Yngvi/Ing. However, the expected Norse version of this name, *Austra, does not exist in our sources. Is this because an old compound like Austra-Freyja was forgotten in favor of simply “Freyja”?

Let it be known that I am not claiming Ēostre is the true Freyja, only that the information is too scant to be confident about anything.

Frigg and Freyja share striking similarities.

Frigg’s husband in Old Norse is named Óðinn and Freyja’s husband is named Óðr, which are two names derived from the same root. Óðinn and Óðr are both prolific wanderers disappearing for long periods of time, and both women are attested as sleeping with other men while their husbands are absent.

Frigg and Freyja both own wearable bird skins (items associated with valkyries) which allow the wearer to fly. Both characters lend their bird skins to Loki on different occasions. They are also both associated with determining the outcome of battle. The poem “Grímnismál” indicates that Freyja participates in choosing half the slain each day12, for instance, and the Langobard origin myth13 features Frigg (therein called Frea) manipulating Odin (therein called Godan) into choosing the winners of a battle between the Winnili and the Vandals. The similarities abound. Might these similarities exist because both characters were merged at some point in the past?

Playing Devil’s Advocate

Similarities do not necessarily mean that two characters were originally one and the same. Perhaps an alternative theory, just building upon my devil’s advocacy up to this point, could be that Frigg and Freyja were on the path toward a merger in medieval Scandinavia. Rudolf Simek theorizes14 that because the Old Norse word for Friday (“Frigg’s Day”) was imported from Old Saxon, it could indicate that Frigg herself is an import into Scandinavia from a more southerly Germanic tradition, though still prior to the Norse period. In this case, a precursor to Freyja could theoretically pre-date Frigg in the north. If so, maybe Freyja was once a goddess more like Ēostre who began to take on more and more Frigg-like attributes over time. Could the idea of an oncoming merger not also explain the loss of her name, reconcile her existence with other Germanic sources, and account for the similarities she shares with Frigg?

To reiterate once more for extreme clarity, I am not claiming that Frigg and Freyja were on a path toward merging in Viking-Age Scandinavia. This is not a rigorously thought-out theory as far as I’m aware, and I am not actually advocating for it.

My intent here is to show that the Frigg/Freya common origin hypothesis, while intriguing, is far from conclusive. The evidence itself doesn’t even necessarily point in a single direction. All we can say definitively is that, within the body of actual Norse myths that have survived into modern times, Frigg and Freyja are separate individuals with total consistency.

Avoiding the Great Goddess

One final point: there has appeared in academia a few times over the years a strange desire to try and merge all female deities back into a single point of origin, yet no similar desire to do so with males. Joseph S. Hopkins15 notes that while the idea of ascertaining some original, matriarchal “Great Goddess” can appear progressive from a feminist standpoint on the surface, this type of theorizing has roots in 19th-century thinking that is anything but feminist and has never been widely accepted in mainstream scholarly discussion. One early proponent of the theory, Johann Bachofen, viewed this notion of an early matriarchal period “as a phase from which mankind needed to ‘evolve’ in order to reach then-modern society.”16 In the end, is it really more progressive to seek an ancient, original goddess than to acknowledge and accept the wealth of attested goddesses that we have? After all, surviving Norse sources name a great deal many more goddesses than gods.

To me at least, the Frigg/Freyja hypothesis smells suspiciously like antiquated Great-Goddess thinking. This is not to say that we must never suspect a common origin between any two women in myth, only that it behoves us to consider our motivations for theorizing and to always be critical of weak evidence.

Pettit, E., trans., The Poetic Edda: A Dual Language Edition, (Open Book Publishers, 2023), p. 291

Pettit, p. 299

Þorgeirsson, H., Árnason, K. (Ed.), Carey, S. (Ed.), Dewey, T. K. (Ed.), Aðalsteinsson, R. I. (Ed.), & Eyþórsson, Þ. (Ed.) (2016). “The dating of Eddic poetry: evidence from alliteration”. In Approaches to Nordic and Germanic Poetry Málvísindastofnun og Háskólaútgáfan, Reykjavík.

“Germanic Religion and Mythology - German and English Vernacular Sources | Britannica.” Www.britannica.com, www.britannica.com/topic/Germanic-religion-and-mythology/German-and-English-vernacular-sources#ref533239.

Harris, Joseph. “Basic Tools.” Old Norse-Icelandic Literature: A Critical Guide, by Carol J. (Ed.) Clover and John (Ed.) Lindow, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2005, p. 100.

Faulkes, A., trans., Snorri Sturluson: ‘Edda’ (London: J. M. Dent, 1987), http://vsnrweb-publications.org.uk/EDDArestr.pdf, p. 86

Faulkes, p. 29

Faulkes, p. 156

Chickering, Howell D. Beowulf: A Dual-Language Edition. New York, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 2006, p. 109

See my post “Norse vs. Germanic” for more information regarding the relationship of Norse mythology to broader Germanic religious belief.

Wallis, Faith (Trans.) (1999). Bede: The Reckoning of Time. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-693-3

Pettit, p. 176

Roberto, Umberto. “Origo Gentis Langobardorum”. Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle. Ed. Graeme Dunphy & Cristian Bratu. Brill Reference Online. Web. 4 Dec. 2023.

Simek, R., Dictionary of Northern Mythology, (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2007). p. 94

Hopkins, Joseph S. “Great Goddess Theory in Ancient Germanic Studies.” RMN Newsletter, no. 14, 2019, pp. 70–76, www.academia.edu/40134430/Great_Goddess_Theory_in_Ancient_Germanic_Studies.

Hopkins, p. 71