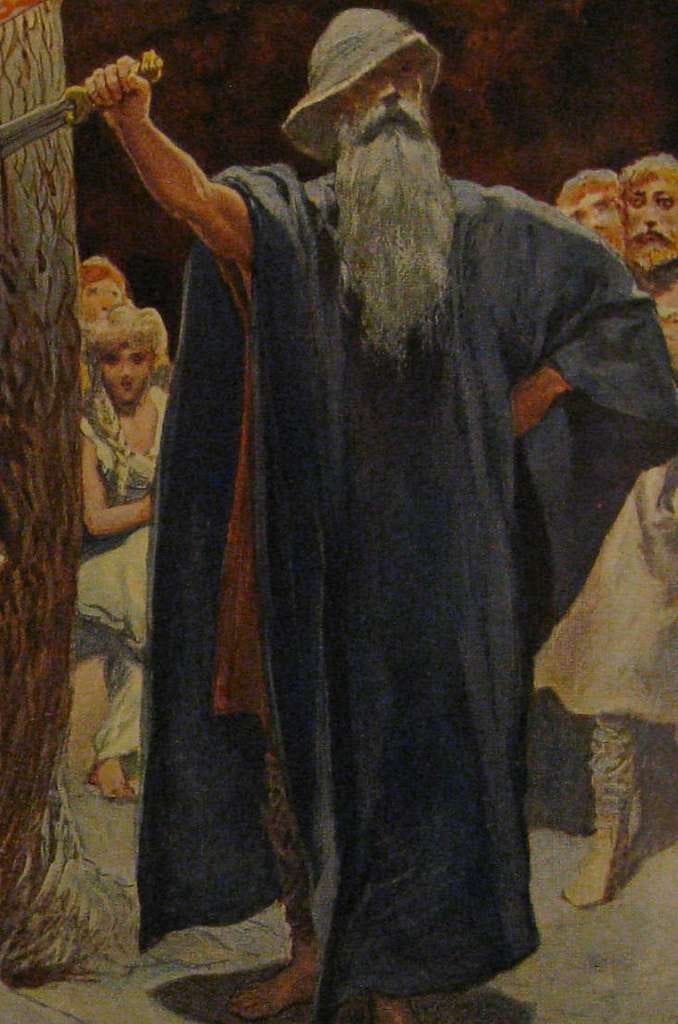

Odin Is Not an Unmanly God

On the overblown association between Odin, seid, and ergi

Ancient Norse tales are full to the brim with characters performing actions we might deem “magic” in our modern vocabulary. Whether it’s animal transformations, neutralizing poison with runes, cursing someone with a magic wand, or divining fate, creating a supernatural effect through ritual is a frequent action taken by gods, monsters, and humans, male and female alike. But whereas magic itself seems to be the domain of all intelligent beings, there is a particular brand of Norse magic called “seid” (seiðr in Old Norse) that is reserved specifically for women (and perhaps any man who doesn’t mind being derogatorily labeled argr “unmanly”1).

Let’s start by acknowledging the fact that nobody has a full picture of what makes the practice of seid especially feminine in the Norse mind2. Snorri Sturluson asserts in his 13th-century Ynglinga saga3 that, by using seid, a person could “predict the fates of men and things that had not yet happened, and also cause men death or disaster or disease, and also take wit or strength from some and give it to others”4. Snorri is of course quick to add that “this magic, when it is practised, is accompanied by such great perversion that it was not considered without shame for a man to perform it”. Exactly why this is the case is left up to speculation.

Being a feminine practice, seid is often described as the magic of seeresses (vǫlur). In Eiríks saga rauða5, there is a famous episode in which a seeress presides over a ritual wherein she sits atop a sort of scaffold surrounded by a group of women. One of those women then delivers a performance of one of many seid-oriented “warding songs” (varðlokur6) she learned from her mother, and the seeress subsequently explains that the beauty with which the song has just been sung has pleased the surrounding nature spirits.

For context however, Norse men do sing, though it is unclear what differences might exist between masculine and feminine singing styles. There are also Norse men described in literature with the power of prophecy who are not portrayed as unmanly. These include the god Heimdall, Sigurd’s uncle Gripir, Thorhall from Þiðranda þáttr ok Þórhalls, and pretty much anyone right on the verge of death. Thus, we can’t ascribe the inherent femininity of seid to prophecy or singing, all else equal. There have been several scholarly attempts at sussing this out over the years, but with such limited available information, the community has not been able to settle on a consensus regarding the complete picture.7

There has also been much written about Odin’s association with seid, and that association has led to a school of thought claiming Odin is either tightly coupled with the Norse concept of ergi (unmanliness) or is even potentially queer. My argument is that both forms of this idea are incorrect, being based entirely upon overzealous source-material embellishment.

Side note: Readers should not interpret this post as a denouncement of queer theory itself, however every theory suffers when its application requires fabricating information. I recognize that a lot of people have forged personal connections to this material and I have no interest in trying to invalidate any of those connections. That said, if we want to understand Odin in the way the original storytellers and their primary audiences would have, then we must view him through their cultural lens and not our own. In this post I will be discussing ancient ideas as they were recorded, without embellishment, and with no desire to tear down anyone’s personal beliefs.

Now let’s trace Odin’s association with seid back to its source.

Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus, in his 12th century work Gesta Danorum8, provides a euhemerized account of the death of Baldr and Odin’s subsequent consultation of a seeress. The seeress foretells that Baldr will be avenged by a future son that Odin must father with a princess called Rind. However, Rind does not want to marry Odin, no matter how many disguises he dons or impressive feats he accomplishes because she is not attracted to old men. So in order to fulfill the seeress’ prophecy, Odin finally disguises himself, as Saxo describes in Latin, “in girl’s clothing” (puellari veste sumpta) and “testifie[s] to knowing the art of medicine” (arte medicam testabatur). In this disguise he calls himself Wecha and is appointed as Rind’s attendant. When Rind eventually falls ill, Odin has her restrained on a bed so that he can administer some unpleasant medicine and, once everyone else leaves the room, he has his way with her in an assault that results in her bearing the son who will eventually slay Baldr’s killer.

Though Saxo does not use the word seid in his euhemerized retelling of a story that is otherwise mostly lost to history, this medicine-woman disguise is clearly a gloss for a seiðkona (seid-woman) of some sort. Confirmation can be found in a line from the 10th-century poem Sigurðardrápa by Kormákr Ǫgmundarson which reads “Ygg (Odin) used seid to get Rind” (seið Yggr til Rindar).

Next we turn our attention to the poem Lokasenna, and particularly to stanza 24. For context, Odin has just accused Loki of spending eight winters below the ground in the form of a milking cow and a woman, and of bearing children, all of which he asserts is an “unmanly way to be” (args aðal). Loki responds in kind by pointing out Odin’s own unmanly behavior:

En þik síða9 kóðu Sámseyju í, ok draptu á vétt sem vǫlur; vitka líki fórtu verþjóð yfir, ok hugða ek þat args aðal!

But they say you practiced seid on Samsø, and struck upon a drum(?) like seeresses; in wizard’s likeness you went over/among mankind, and I thought that an unmanly way to be!

Scholars have noticed10 that the word I translated to “wizard” here, vitka, appears to be the origin of Saxo’s Latinized Wecha. The implication, of course, is that the event referenced in Lokasenna is the same event described in Gesta Danorum.

Beyond this, Odin’s knowledge of seid is mentioned by Snorri in Ynglinga saga after his assertion that Freyja first introduced the practice among the Æsir. It is never explicitly stated that Freyja personally mentored Odin in seid, only that he became acquainted with the practice and that it was taught to all of the goddesses.

There is, of course, no reason to believe Snorri had any reason to associate Odin with seid apart from what he knew of Lokasenna, Sigurðardrápa, and perhaps some version of the story told by Saxo. In other words…

Odin’s association with seid is based entirely upon a single event in which he used it as a mechanism for achieving sex with a woman.

The idea that Odin’s behavior in Lokasenna comprises an isolated incident is further supported by Frigg’s opinion as given to Loki and Odin in the following stanza (25):

Ørlǫgum ykkrum skylið aldregi segja seggjum frá, hvat it æsir tveir drýgðuð í árdaga; firrisk æ forn rǫk fírar.

You two should never talk publicly about your fates, (of) what you two Æsir perpetrated in days of yore; let people leave behind prior fates.

The point is that Odin’s practicing of seid on Samsø is something that happened í árdaga (in days of yore, once upon a time, long long ago). It is not described as a behavior he is currently engaged in. Whereas several myths continue to portray Loki as engaging in argr behavior in the mythic present, this does not hold true of Odin11.

Odin is overwhelmingly treated by ancient sources as a masculine character. He is constantly engaged in war-related activities and is involved with several different women.12 In fact the first two aspects of seid as practiced by Snorri’s euhemeristic Odin (specifically predicting peoples’ fates and predicting future events) are things that the mythological Odin does not do, but turns to seeresses for instead. The poems Vǫluspá and Baldrs Draumar, for instance, portray an Odin who specifically does not know fate and the future, and must question seeresses to obtain this information. If Odin was indeed so comfortable with seid, why not simply do these things himself?

On the topic of differences between Ynglinga saga’s euhemeristic Odin who is a human wizard-king and the mythological Odin who is a god, we can also examine Snorri’s claim that when wizard-king Odin engaged in shapeshifting, “his body lay as if it was asleep or dead, while he was a bird or an animal, a fish or a snake, and travelled in an instant to distant lands, on his own or other people’s business.” This claim has caused various scholars (especially archaeologists) to draw a connection between Odin and either Sámi or Siberian forms of shamanism. However, as Annette Lassen reminds us:

…the interpretation of Odin as a shaman is not generally accepted. Of studies that argue against the shamanistic interpretation of Odin, I can, at random, mention Jere Fleck (1971a: “The ‘Knowledge-Criterion’ in the Grímnismál: The Case against ‘Shamanism’”), Einar Haugen (1983: “The Edda as Ritual: Odin and his Masks”), and Jens Peter Schjødt (2001: “Óðinn: Shaman eller fyrstegud”, Odin: Shaman or God of Chieftains). And in connection with the sagas of Icelanders, François-Xavier Dillmann argues against the interpretation of magic (seiðr) as a form of shamanism (1992, 2006).13

There are two main problems with the shaman interpretation. Firstly, the fact that Odin’s behavior may recall other cultures’ shamanic behavior from time to time is by no means an indication that he should be considered a carbon copy of shamans from those other cultures.14 If we notice, for instance, that Odin has animal helpers as some foreign shamans do, we can not infer solely from this that he has anything else in common with those shamans.

Secondly, and with particular regard to Snorri’s wizard-king Odin, Lassen explains that:

This part in the description of Odin thus appears to result from euhemerism […] The passage of Odin’s outer-body journey appears to have been inspired by the shamanism of the Sámi and perhaps by descriptions of Greco-Roman gods and is therefore not usable as a model with which to understand Odin as a shaman, and therefore hardly of Odin as a “shaman god”. A depiction of Odin as a human shaman does not appear to be part of the native Norse tradition.15

This is extremely important because the notion of Odin as an unmanly or queer character relies heavily upon the shaman interpretation (though it completely ignores Snorri’s claim that seid is shameful for men). Unfortunately this interpretation is rejected by the academic community at large, albeit with the acceptance that Odin does at times seem to bear individual similarities to foreign shamans.

Continuing the story as told in Gesta Danorum, when the Æsir catch wind of Odin’s antics, they consider his masquerade as a woman (not the assault on Rind16) to have been so shameful that they banish him from their society. Some years later, after things have blown over, he is reinstated as chief of the Æsir. An important takeaway is that, if a single instance of unmanly behavior is considered sufficient to dethrone and banish Odin, we certainly can not assume that he is regularly engaged in that sort of behavior, otherwise he would be regularly banished, each instance making him an unfit chief of the gods. Again we are led to believe that Odin’s involvement with argr behavior is limited to a purpose-driven, isolated incident.

Isolated incidents of taboo violation are not otherwise unheard of in Norse mythology. The notion calls to mind the poem Þrymskviða and Thor’s own involvement with cross-dressing. In that context, Thor explicitly pushes back against Heimdall’s suggestion that he should disguise himself as Freyja in order to retrieve his stolen hammer. From stanza 17:

Þá kvað þat Þórr, þrúðugr Áss: | ‘Mik munu Æsir argan kalla, | ef ek bindask læt brúðar líni!’

Then spoke Thor, the powerful god: “The Æsir will call me unmanly if I let myself be bound in bridal linens!”

However, Loki is able to remind Thor that the safety of the world hangs in the balance so long as his hammer is missing. Understanding this to be true, Thor reluctantly agrees to the plan. It would appear that gender taboos, while quite serious in the Norse mind, are to be taken as less important than the preservation of cosmological order. The underlying challenge to the audience in both of these accounts seems to be, “what would you do if the only way to fulfill your expectations as a man was to betray your own masculinity?” For a society so heavily (even legally) entrenched in binary gender roles, it is a deep and probing question.

Academics such as Brit Solli (who I discuss here as perhaps the most well-known advocate of the queer Odin theory), as well as Neil Price have accepted the outmoded idea that Odin’s association with seid indicates that he is a shaman, and then, through the lens of non-Norse shamanism which sometimes involves non-binary sexuality, have concluded that he is a queer god17. Unfortunately, this application of queer theory (or just argr-ness) to the character of Odin requires drawing conclusions based upon embellished or misunderstood information. For instance, as Clive Tolley astutely notes:

…we have no evidence for the integration of sexual activity into the human practice of seiðr, even if it was regarded as somehow argr to practice it.18

From here there is a risk of this post beginning to sound like an anti-Solli post, which it is not meant to be. However, it is worth talking through some of the analysis that has lead to the conclusion that Odin is an argr, shamanic seid-man and where the problems with that analysis lie.

Solli writes, for instance, that “By going through [the ordeal of hanging for nine nights on a tree, Odin] acquired knowledge of the runes and the songs to be used when doing seid.” The second half of this claim is fabricated. There is no source-material description of Odin learning seid-oriented songs while hanging from the tree. Whereas he does “take up the runes” (nam ek upp rúnar) after his ordeal, runes themselves are not exclusive to seid, the songs Odin mentions learning in the subsequent stanza are explicitly said to have been taught to him by a (jotun?) man named Bǫlþórr19, and there are various attestations of males performing magic by way of both runes and songs that we are not given to understand as being unmanly (i.e., not seid-oriented).

But why fabricate this information, especially when it seems in opposition to Snorri’s assertion that seid was taught to the Æsir by Freyja? The answer is that Solli has already accepted the interpretation of Odin’s self-sacrifice as a “shamanistic initiation ritual”20 from the outset. In her mind, this means that it must have been a venture into seid. Rather than building a theory from textual evidence, Solli begins with a conclusion and then retrofits the text to match. To her, the information she’s invented was only missing in the first place.

Strangely, only a few paragraphs later, Solli reminds us of her belief that “Odin had learned seid from the vanir goddess Frøya.”21 Are we to understand that Freyja taught him seid but none of the songs needed for doing seid? Or can this problem be solved by assuming that it was Freyja who hanged Odin in the first place in order to teach him seid? Already we are tempted to continue inventing new information in order to explain away the fact that our theory does not match the source material. Were we to publish it, uncritical scholars of the future might say, “because Odin’s sacrifice is a shamanic initiation ritual wherein he learned seid, Freyja must have been the one who hanged him.” This is why we can not begin with a conclusion; we must build a conclusion from evidence.

Solli ultimately concludes that “Odin had to be a queer god, because only by his doing seid and being queer could the world continue to exist. That androgyny was considered as a divine trait is known from several cultures and religions.”22

The first problem with this, as I’ve already mentioned, is that the assumption of Odin’s queerness is based upon the idea that he embodies foreign ideas about shamanism, which in turn is an idea founded entirely upon a euhemeristic description by Snorri as well as Odin’s association with a misunderstood concept of seid, which he used on only one recorded occasion in a purpose-driven attempt to achieve heterosexual sex. Beyond this, there are no attestations of the mythological Odin actually performing seid or actually doing anything particularly unmanly.

It is true that Odin’s foray into seid was done in service of fate, and indeed Thor’s taboo violation was likewise necessary for the preservation of the world. However, a choice between the lesser of two evils (which is how both narratives are presented) is hardly justification for labeling a character’s sexual identity. That Odin had to break a taboo to preserve cosmological order is not sufficient to claim that he was or was not queer.

Solli is correct that several cultures and religions (even ancient ones) recognize androgyny as a divine trait. But this can not be taken to mean that every ancient religion espoused this idea, much less that any given deity in the ones that did can be ascribed a divine androgyny. The application of queer theory to the character of Odin in particular relies upon many layers of interpretation, assumption, and embellishment that have been long refuted. When we consider the source texts themselves, conclusions such as Solli’s inevitably fail because they can not stand up to scrutiny. I have included several more examples in the footnotes (please read them)23.

The truth is that Norse mythology does frequently deal with the concepts of sex and gender. The character of Loki, for instance, exhibits so-called unmanly behavior quite often and is therefore a fascinating case study in the topic. However, the Old Norse language has no vocabulary for describing divine androgyny, acceptable queerness, or non-binary gender/sexuality. What it has in this space are the nouns níð (accusations of shameful behavior) and ergi (as well as its derivatives such as argr) which are not benign; they are always potent, potentially life-altering insults.24 It is hard to believe that any given society places much stock into ideas that it does not have linguistic tools for describing. Once any idea does become important, the vocabulary naturally follows.

Whereas it is true that humans have always been humans and ancient Norse people certainly existed who experienced feelings we would term something other than heterosexuality in modern vocabulary, the study of sexuality in Norse society is done a disservice by accepting wild speculation as fact, especially when it contradicts the ancient record we have. Odin is no more an argr god than is Thor, which is to say that he is no argr god at all. He is likely not even a continual seid-user. We are all studying the same source material so, feel free to ask yourself: outside of the Rind/Samsø episode, how often have you seen the myths associating Odin with seid or ergi?

If you are having trouble coming up with examples, Jens Peter Schjødt may be able to shed some light upon why:

…any sort of queer theory in connection with Óðinn rather tends to qualify as some sort of modern myth in accordance with popular ideas in the contemporary world, but hardly with the norms of one of the most homophobic societies one can possibly imagine, that of the Germanic Iron Age. […] There is nothing to indicate that Óðinn had a ‘dual sexuality.’ Quite on the contrary, there are elements that are part of his semantic center that make it highly unlikely that this would be the case.25

The simple answer, then, is that the argr Odin is not a source-supported idea.

Ström, Folke. Níð, Ergi and Old Norse Moral Attitudes. Viking Society for Northern Research, 1974. (Additionally, see my post “Loki, Gender, and Sexuality in Norse Society” for more on this topic.)

Schjødt, J. P., “Óðinn – The Pervert?”, Res Artes et Religio: Essays in Honour of Rudolf Simek, (Leeds: Kismet Press, 2021). p. 541. – “We do not know what it was about this practice that caused associations with the female sphere, but, as is also mentioned by Snorri, the phenomenon of ergi no doubt plays an important role here…”

Finlay, A. and Faulkes, A. trans., Snorri Sturluson: Heimskringla. Vol. 1, Viking Society for Northern Research, University College London, 2011, p. 11.

Whether this description is fully accurate is questionable. Snorri’s writings are two centuries removed from paganism in Iceland and, while many of his claims in Y.S. appear rooted in historicity, much of the narrative is quite obviously fabricated.

“Eiríks saga rauða.” Heimskringla.no, https://heimskringla.no/wiki/Eir%C3%ADks_saga_rau%C3%B0a. Accessed 22 Jul. 2024.

There are various forms of this word and therefore various possible interpretations. Three attested forms are varðloka, varðlokka, and urðarlokka, respectively “ward lock”, “ward lure,” and “fate lure”. Cleasby/Vigfusson asserts that this is the origin of the word “warlock”, though in the Scots/English sense the meaning has shifted from the spell to the wizard himself (https://cleasby-vigfusson-dictionary.vercel.app/word/vard-lokkur). The component varð- may also be related to vǫrðr, in which case the meaning of varðlokka would be “guardian spirit lure”. This seems an appropriate fit for the narrative in Eiríks saga rauða given the goal and result of the ritual performance.

Clive Tolley believes it is because outside spirits enter and subjugate the seid performer, and this subjugation would be considered shameful for a man. – Tolley, C., Shamanism in Norse Myth and Magic. (Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2009), p. 159.

Friis-Jensen, K., ed., and Fisher, P., trans., Saxo Grammaticus: Gesta Danorum: The History of the Danes, 2 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015). Vol I, section 4.

This translation accepts an emendation of síga (to sink) to síða (to practice seid). Even if this is incorrect, the implication remains the same. Odin strikes an object as a seeress would, and the act of sinking itself may also imply seid as this is the final action taken by the seeress after delivering her prophecy at the end of Vǫluspá.

For example: Hall, Alaric. “The Meaning of Elf and Elves in Medieval England” 2004. University of Glasgow. p. 149. Also see Shjødt p. 542: “If we accept that the myth told by Saxo is actually the one that is hinted at here – and I see no reason why we should not – then we can just look at history.”

There is actually an interesting conversation to be had about Odin’s choice to galavant with women at times when Thor is doing battle as discussed in Hárbarðslóð st. 15-18. These actions are often contrasted in Norse narratives and poetry with the implication being that the man who is spending his time with women is not showcasing bravery as he ought. However, this should be taken in the context that Odin describes himself as both wreaking slaughter and having his choice of girls in stanza 16, and makes mention of several of his own exploits in battle throughout the poem. There is no implication here of sexual ergi.

Apart from having either married or fathered children with at least three different women (Frigg, Jord, and Rind), Odin boasts about several further heterosexual conquests. Consider Hárbarðslóð st. 18 (Pettit’s translation): “We had sparky women, if they submitted to us; | we had knowing women, if they were nice to us; | out of sand they plaited ropes | and out of a deep dale | they dug the ground; | I alone became superior to them by scheming, | I slept beside those seven sisters, | and I had all their lust and love-play!”

Lassen, Annette. Odin’s Ways: A Guide to the Pagan God in Medieval Literature. Routledge, 2022. p. 37

Schjødt, p. 546: “No doubt, there is a kind of ‘family resemblance’ between the techniques of all magicians throughout the world. This, however, does not make all magicians shamans, or all such techniques similar to a kind of shamanism.”

Lassen, p. 158.

Saxo explains that, “through adopting actors’ tricks and women’s duties, [Odin] had brought the foulest of slurs on [the Æsir’s] hallowed reputation.” (Saxo, pp. 169-170)

Solli, B. (2008). Queering the Cosmology of the Vikings: A Queer Analysis of the Cult of Odin and “Holy White Stones.” Journal of Homosexuality, 54(1–2), 192–208.

Tolley, p. 164.

Pettit, E., trans., The Poetic Edda: A Dual Language Edition, (Open Book Publishers, 2023), pp. 112-113.

Solli, p. 199.

Solli, p. 202.

Solli, p. 200.

Additional examples:

Solli states that Odin “is the manliest god of warriors, but he is also the unmanly master of seid. This paradox has not been satisfactorily explained in earlier research” (p. 195). There is no paradox. As I continue to reiterate, we know of only one instance in which Odin used seid, which he did in order to impregnate a woman as a last resort after other attempts had failed.

Solli goes on to ask, “How could Odin do seid without losing his position as master of the warriors? In other words, there is ambivalence in Odin’s gender status that is difficult to understand” (p. 195). Yet the narrative we have explains that Odin did lose his position as a consequence of his foray into seid, exactly as we would expect.

Citing earlier scholars such as Eliade and Buchholz, Solli writes, “there is no doubt that the god Odin, when practicing seid, travels to the world beyond or wherever he wants to go” (p. 196). There is plenty of doubt. I contend that there are zero attestations of Odin traveling to the “world beyond” by means of seid (much less even using seid outside the Rind incident). Rather, his descent into Hel is performed on horseback. Why should we interpret this as a shamanic spirit-journey when, upon arrival, he must meet with an actual seeress (i.e., a real seid practitioner) in order to learn something about the future?

Solli muses that “Snorre Sturlason describes Odin as the master of seid, but it is remarkable that Snorre never mentions the hanging sacrifice. […] Why did he not include the hanging sacrifice in his narrative when he described Odin as the master of seid?” (pp. 196-197). Solli never posits an answer to the question, but the answer is probably no more complicated than that Snorri had no reason to believe Odin’s hanging had anything at all to do with seid. Solli’s musing clearly takes as a given the idea that Odin’s hanging is a seid-oriented, shamanic ritual, which is little more than conjecture.

Solli takes issue with Strömbäck’s opinion that “ecstasy and loss of control represented weakness and thus, femininity[;] women were both impure and out of control.” She notes that “conceptions of female impurity do not exist in Old Norse mythology. However, such conceptions do exist in Judaic-Christian and Islamic cosmology.” Ironically, Solli’s entire paper can be refuted with the exact same approach: conceptions of socially-acceptable, shamanic queerness do not exist in Old Norse mythology. Solli is willing to take a source-literal approach when disagreeing with other scholars and is happy to call out the fact that not all religions are the same in that context, but is perfectly happy to accept embellishments and to assume that concepts found in non-Norse cultures can be applied to Norse narratives when doing so is necessary to support her own conclusions.

Solli writes, “the [self-sacrifice by hanging] involved pain and ecstasy, [and the pain] is not only agony and torture for the sake of sacrifice but also a way of provoking the necessary ecstatic trance, that was a precondition for the soul-journey Odin made to Hel.” She then quotes Buchholz in saying that “in a condition of perfect ecstasy, after nine days of pain, only then Odin was able to learn the magic, the wisdom and the knowledge of poetry,” and goes on to relate Odin’s experience to autoerotic asphyxiation due to the alleged ecstasy experienced while choking. Of course, “ecstasy” (whatever that is really supposed to mean) is never mentioned anywhere in our sources as being connected to Odin’s hanging, and as Tolley has reminded us, there is no real evidence of a sexual component to seid. All we are told is that Odin screamed when taking up the runes (œpandi nam). Note how a single instance of the word “screaming” has been interpreted as an expression of ecstasy, which then turns into a sexual, shamanistic soul-journey to Hel, which then somehow becomes a requirement for knowing poetry. These conclusions are drawn from layer upon layer of embellishment and uncritical interpretation. Apart from this, Schjødt reminds us (p. 545) that: “There is no doubt that Óðinn, as a god having to do with mental aspects of war, among other things, will be able to arouse some sort of ecstasy in his warriors. The only form of ecstasy that can be connected to Óðinn, however, is exactly the frenzy that is known from all warrior societies through the ages. It has nothing to do with ‘sex’ or ‘sexual ecstasy,’ not to mention ‘dual sexuality.’ It appears exclusively in the context of war.”

In what is perhaps one of the most brazenly unsupported interpretations ever published regarding Adam of Bremen’s claim that animals and men were hanged as part of the proceedings at the Uppsala temple, Solli says this: “In Adam of Bremen’s narrative all the men and animals die in the hanging. But what about the idea that the men were not supposed to die? Maybe these men were aspiring shamans? Some died because they could not take it. They overdid the ecstasy and never returned from their soul-journey; they simply perished. Maybe the whole ado was about finding the most powerful seidman/shaman? The man, who survived the soul-journey, who came back from the initiation ritual, the hanging, was to become the tribe’s new shaman. Every nine years they had to find a new and powerful shaman, because only then could the world continue to exist.” These suppositions are based upon absolutely no evidence. Alternatively those men were just being sacrificed as Adam stated, similar to King Vikar in Gautreks saga who is stabbed with a spear and hung in an explicit human sacrifice dedicated to Odin. (See my post “The Norse Afterlife Part I: How to Get to Valhalla”).

At a high level, Solli makes a concerted effort to to show that Norse societies both required and desired members of a queer, shamanic class (or even gender, which would take another whole post to discuss sufficiently) because, only with these seid-men “could the world continue to exist.” It would appear that Solli’s argument accidentally devalues the role of actual, historical seid-women in Norse society, fully usurping their attested, important role with that of a biological male.

Again, see Ström, 1974.

Schjødt, p. 544.

This is very good and excellently written and insightful. Thanks very much!

I found you through Reddit, and as someone who practices a Norse inspired religion, it was a must-follow.