Ancient Runes and Rune Magic

An introduction to what we really know about the history of runes and their magical applications

This post will not teach you how to do any magic. Instead, I’ll be providing an overview of what our sources say about this topic and what they don’t, as well as showcasing a few examples. For a more in-depth read, I recommend Runic Amulets and Magic Objects by MacLeod and Mees (2006)1.

This post will also not teach you how to write with runes. For a more extensive history of runes, I recommend starting with Runes: A Handbook by Barnes (2012)2.

Now let’s get started!

What are runes?

A rune is any letter (or message!) inscribed with any ancient Germanic alphabet (see below) that was used before the adoption of the Latin alphabet (a.k.a, the ABCs) that we use today. Because runes are letters, they are used to write words and sentences. By the same token, any symbol that can not be used as a letter in a written word is therefore not a rune. So, for instance, the Valknut, Ægishjálmur, and Vegvísir are all not considered runes.

Continuing this idea, beginners often ask questions like, “What’s the rune for Odin” or, “Is there a rune symbolizing Ragnarok?” The answer to all questions like this is, historically, there is no single rune for any of these things. Runes are letters used to spell words, not a pictographic library of symbols representing every imaginable concept.

There have also been a few alphabets created in modern times using symbols inspired by historical runes, and these are often called “runes” themselves. However, modern inventions are beyond the scope of this post.

What is a Germanic alphabet?

The word Germanic refers to a family of related languages that share certain linguistic features. In modern times this family includes English, German, Dutch, Danish, Norwegian, Swedish, Icelandic and a few others. These languages are related because they all descend from a common ancestor language called Proto-Germanic that developed in southern Scandinavia somewhere after 500 BC and was splitting into different branches by about 200 AD.3

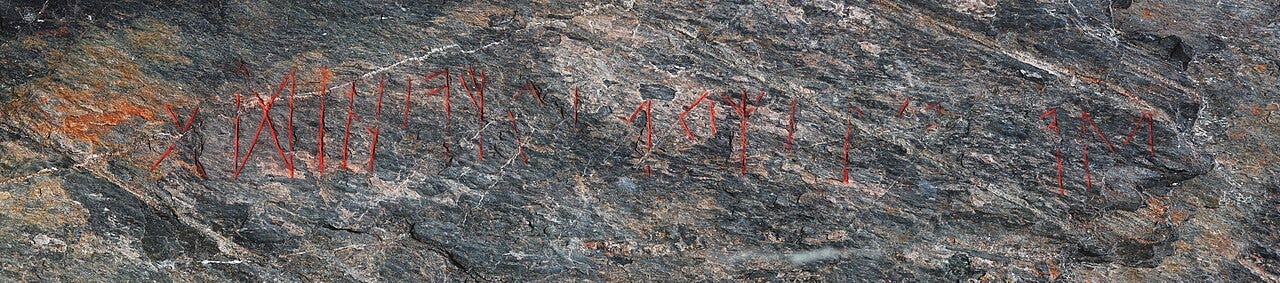

For a long time, the oldest known runic inscriptions could only be dated to the approximate end of this period. However, in 2021, a runestone was discovered in Norway that has been dated to as early as 1 AD4, indicating that the practice of runic writing had likely already been established, perhaps even by centuries at this point.

These early inscriptions are written in an alphabet that we call the Elder Futhark. Because it was an alphabet developed by Germanic(-speaking) people for writing a Germanic language, we can call it a Germanic alphabet. More specifically, the language of the earliest-dated inscriptions is likely following the transition from late Proto-Germanic into early Proto-Norse (which would eventually develop into Old Norse, the language of the vikings.) As you can probably imagine, there is some gray area when it comes to labeling in the transitional years between two recognized language stages.

The Elder Futhark alphabet spread throughout Germanic-speaking territory and was modified to fit different use cases as language diverged over time and distance. Along the North Sea coast, Elder Futhark evolved into the Anglo-Frisian Futhorc which was carried to England during the Anglo-Saxon migrations and remained in use there until the 11th century. By the beginning of the Viking Age in Scandinavia, Proto-Norse had evolved into the North-Germanic dialect continuum we now call Old Norse. For reasons that are not fully known, there was a push among Old Norse speakers at this time to replace the Elder Futhark alphabet with a new runic alphabet we call the Younger Futhark.

Over time, in all of these contexts, innovations were made to the ways people inscribed runes locally. Sometimes new runes or new variations were invented to add clarity or to fit specific use cases and, eventually, all of these runic systems were abandoned in favor of other alphabets (usually Latin). But before that happened, Germanic speakers were writing with characters that were ultimately descended from the Elder Futhark. Thus all of these earlier systems can be called both “Germanic alphabets” as well as “runes”.

Where did runes come from?

According to Norse mythology, the origin of the runes is cryptically given in the poem Hávamál. Consider stanzas 80, and 138-1395:

80: It’s proven then, when you enquire of the runes, those of divine descent, those which mighty powers made and Fimbulþulr coloured; [a foolish man] does best then if he keeps quiet.

138-139: I (Odin) know that I hung on a windy tree for all of nine nights, wounded by a spear and given to Óðinn, myself to myself, on that tree of which no one knows the kind of roots it runs from. They blessed me with neither bread nor horn, I peered down, I took up runes, screaming I took them; I fell back from there.

More scientifically, many of the runes bear striking resemblance to their counterparts in alphabets that were already being used to write languages such as Latin and Greek at the time of the emergence of Elder Futhark. There is no academic consensus on a complete picture of how the runes came to be, however it is a likely story of borrowing from and innovating on the letterforms of other, pre-existing alphabets.

What does futhark mean?

Similar to the way the word alphabet comes from the names of the first two Greek letters (alpha and beta), the word futhark comes from the sounds represented by the first six letters of the Elder Futhark rune-row in standard order:

ᚠ (“f”), ᚢ (“u”), ᚦ (“th”), ᚨ (“a”), ᚱ (“r”), ᚲ (“k”).

The Younger Futhark alphabet is similar. This is also why we call the Anglo-Saxon alphabet the Futhorc. In that system, the second vowel represents an “o” sound, and the sixth letter can make either the “k” sound or the “ch” sound, depending on context. Some people prefer to pronounce the word futhorc as “foo-thorch” to capture this nuance.

What are the runes’ names and how do we know them?

In English, we have a song that we use to teach children the Latin alphabet, set to the same tune as “Twinkle Twinkle, Little Star” and “Baa Baa, Black Sheep”. Similarly, speakers of older Germanic languages had poems that probably functioned as mnemonic devices, helping them remember the order and names of the runes. To be clear, there is good evidence that rune poems had greater cultural or religious significance beyond their simple, mnemonic function, as evidenced by their content and composition, and the fact that runes were believed to have a divine origin. But any sort of alliterative poem will also work well for assisting with memorization.

There are three main rune poems that have survived from pre-modern times: an Anglo-Saxon rune poem, a Norwegian rune poem, and an Icelandic rune poem. Both the Norwegian and Icelandic poems deal with the Younger Futhark, while the Anglo-Saxon poem deals with the Futhorc. This means there are no attested sources telling us the names of the Elder Futhark runes. Linguists have instead been forced to use the similarities we find among the surviving poems in light of what we know about how sounds change over time and some hints from the Gothic alphabet in an attempt to reverse-engineer the names of the Elder Futhark runes.

For this reason, different sources will sometimes label Elder Futhark runes with slightly different names. Certain names are harder to confidently reconstruct than others (especially where the rune poems disagree), and different dialects pronounce words with various subtle differences. But here is a basic version of what we have, as provided by R.I. Page6 (with meanings normalized by me combining Page’s information with Barnes’7):

Elder Futhark

ᚠ - *fehu, cattle (culturally signifying wealth)

ᚢ - *ūruz, ?wild ox

ᚦ - ?*þurisaz, giant/monster (an earlier version of the Norse mythological þurs)

ᚨ - *ansuz, god

ᚱ - *raidō, ride

ᚲ - *kauna8, a boil

ᚷ - *gebō, gift

ᚹ - *wunjō, joy

ᚺ or ᚻ - *hagalaz, hail

ᚾ - *naudiz, need (often signifying affliction)

ᛁ - *īsa-, ice

ᛃ - *jēra-, (good) year, harvest

ᛇ - *ī(h)waz/*eihwaz, yew tree

ᛈ - *perþ-, meaning unclear

ᛉ - *algiz, ?elk

ᛊ or ᛋ - *sōwilō, sun

ᛏ - *tīwaz/*teiwaz, the god Tiw/Týr

ᛒ - *berkanan, ?birchwood

ᛖ - *ehwaz, horse

ᛗ - *mannaz, man/human

ᛚ - *laguz, water, liquid, lake

ᛜ - *ingwaz, the god Ing/Ynvi (Freyr)

ᛟ - *ōþala-/*ōþila-, inherited possession

ᛞ - *dagaz, day

Younger Futhark

ᚠ - fé - cattle (culturally signifying wealth)

ᚢ - úr - iron or rain

ᚦ - þurs - ogre/monster (often synonymous with jǫtunn)

ᚬ - ás - any male member of the æsir clan of gods

ᚱ - reið - ride

ᚴ - kaun - ulcer

ᚼ - hagall - hail

ᚾ or ᚿ - nauðr - need (often signifying affliction)

ᛁ - ísa or íss - ice

ᛅ or ᛆ - ár - plenty

ᛋ or ᛌ - sól - sun (also the name of a Norse deity)

ᛏ or ᛐ - týr - the word god generally, or more specifically the god Týr

ᛒ - bjǫrk or bjarkan or bjarken - birch

ᛘ - maðr - man/human

ᛚ - lǫgr - sea

ᛦ - yr - yew tree9

Note that there are fewer Younger Futhark runes than there are sounds in Old Norse. In this context, many of these runes stand for multiple sounds. For instance, ᚢ can represent any rounded vowel such as “u”, “o”, “ø”, and “y”, as well as the “v” sound when it occurs at the beginning of a word10.

Anglo-Saxon Futhorc

ᚠ - feh or feoh, cattle (culturally signifying wealth)

ᚢ - ūr, aurochs

ᚦ - þorn, thorn

ᚩ - *ōs, anciently a god, but possibly “mouth” in the rune poem

ᚱ - rād, ride

ᚳ - cēn, torch

ᚷ - gyfu, gift

ᚹ - wynn, joy or mirth

ᚻ - hægl, hail

ᚾ - nēod, need (often signifying affliction)

ᛁ - īs, ice

ᛡ or ᛄ - gēar, year (the “g” here is pronounced like a consonant “y”)

ᛇ - īw, yew tree

ᛈ - peorð, meaning unclear

ᛉ - ilcs or eolh, ?elk’s (signifies the “x” sound as in box)

ᛋ or ᚴ - sigel, sun or possibly “sail” in the rune poem

ᛏ - ti/tiw, the god Tiw possibly represented by Mars in the rune poem

ᛒ - beorc, birch

ᛖ - eh, steed

ᛗ - mann, man/human

ᛚ - lagu, lake

ᛝ - ing, the god Ing (synonymous with Norse Freyr, signifying the “ng” sound)

ᛟ - œdil or ēðel, inherited land of native country (signifies an “ø” or “œ” sound)

ᛞ - dæg, day

ᚪ - āc, oak

ᚫ - æsc, ash tree (the “sc” here is pronounced like modern “sh”)

ᛠ - ēar, grave or soil (signifies a diphthong like “æ-a”)

ᚣ - ȳr, ?yewen bow

Again these are just the basics, not an exhaustive guide. Old English has a few other runes that are not always used and are shrouded by a bit more uncertainty so I have not included them here. There are also additional variations on the Younger Futhark that came later in the medieval period and even some more unique runic systems (such as Dalecarlian Runes11) that I have not mentioned.

Was Elder Futhark ever used by any vikings?

To be clear, “viking” was only one of many jobs a person could have in medieval Scandinavia. People who engaged in viking were just a subset of the broader population we call “Norse”. Runes were used by anyone who could write, not just the raiders and traders. Additionally, the act of raiding was technically in practice much earlier than what we call “the Viking Age”. So you’ll have to decide for yourself whether or not you think Germanic-speaking raiders from before 793 AD should count as “vikings.”

But with that out of the way, there actually are a sparse few inscriptions containing Elder Futhark runes from Scandinavia during the Viking Age, although these often use Elder Futhark runes in non-standard ways, for example as logographic shortcuts12, or in ways that indicate the carver may not have fully understood the differences between the Elder and Younger Futhark systems13. So even though Elder Futhark does show up here and there during this period, it is very much not the writing system of the time, nor of the people we call “Norse”.

Why does popular media so commonly use Elder Futhark runes in Norse contexts?

Generally speaking, the entertainment industry is more interested in aesthetics than historical accuracy and, for whatever reason, pop culture seems to be obsessed with Elder Futhark. My guess is that this may be because it is easier for a lay person to make a one-to-one transliteration between English letters and Elder Futhark runes. In Elder Futhark, each of the 24 runes stands for a single sound whereas in Younger Futhark, there are only 16 runes and each one has to stand for multiple sounds.

In any case, this phenomenon is certainly frustrating. Some studios will even brag about how much historical research went into a production, but will still make very little effort to actually adhere to historical realities. A few prime offenders in this territory include Ubisoft (makers of “Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla”), Santa Monica Studio (“God of War: Ragnarok”), and the ironically named History Channel (“Vikings” the TV show).

What are ancient runic inscriptions like?

Anything you can imagine a person might write in English with the Latin alphabet could have been written with runes. However, before the introduction of Christianity, Germanic-speaking people didn’t have a culture of creating robust documentation and records, so the most extensive pre-Christian runic inscriptions are found carved on large memorial stones. There are no books or manuscripts that were written in runes prior to the Christian conversion.

Older inscriptions in Elder Futhark tend to be relatively short. Often times we simply find a carving of the alphabet. Other times it’s just a single name. Sometimes we get a longer phrase in the style of “I, So-and-So, give a gift” and sometimes we get gibberish or sequences of runes that don’t make a lot of sense, leaving us to wonder if they had magical significance. A good example is the Lindholm amulet14 which reads:

I, the erilaz, am called Sawilagaz.

AAAAAAAAZZZNN[N]BMUTTT ALU

We are not completely sure what the word erilaz means, but it seems likely related to the English word earl (or jarl in Old Norse), and it seems to have connotations of something like a “runemaster”. The evidence for this is simply that the people carving Elder Futhark inscriptions tend to name themselves as “erilaz” pretty frequently and, if the word is related to earl/jarl, we might expect it to be associated with status in some way.

More often than not, Younger Futhark inscriptions on runestones are Christian in nature, though some are not, and these will sometimes invoke Thor to hallow or bless (vigja) the runes. For example, the Velanda stone15 reads (in my own translation):

Þyrvé reisti stein eptir Ǫgmund, bónda sinn, mjǫk góðan þegn. Þórr vígi.

Þyrvé raised this stone after Ǫgmundr, her husbandman, a very good thegn. Thor bless.

Most commonly, Younger Futhark inscriptions in stone take the above form: “So-and-So raised this stone in memory of Such-and-Such”. However there are some that include more information, such as the Rök stone16, which features the longest runic stone carving so far discovered and seems to preserve a record of some ancient memories in a pagan style.

Younger Futhark inscriptions can also resemble graffiti, and are sometimes very crude. The likely phrase “Halfdan carved these runes” (a Viking Age equivalent of “Halfdan wuz here”) was etched into a parapet inside the Hagia Sophia17, possibly by a member of the Varangian Guard, and the Gamlebyen bone18 from Oslo features the lovely phrase “Óli is unwiped and f*cked in the anus”.

In terms of historical usage, runes were used to write everything from the sacred to the mundane and even the profane. They were simply an alphabet after all.

Are runes magical?

What exactly is magic in a social context where secular/scientific philosophy is not competing with religious philosophy?

Whether runes are magical is a tricky question to answer because a simple yes or no omits lots of important nuance. The Proto-Germanic origin of this word is rūnǭ, and it means “secret” or “mystery” as well as “written inscription”. It’s not too hard to imagine how the development of writing amongst a previously illiterate people would be associated with secrets and mysteries, and it may not be too far-fetched to guess that the very idea of encoding a message such that it could be preserved unchanging throughout time might seem inherently magical to someone who had never encountered such a thing.

On the other hand, runes were not universally considered inherently pagan, as evidenced by the fact that the Futhorc and the Younger Futhark remained in use for centuries after the conversion to Christianity. Carving them was apparently also not always considered an especially sacred practice as many inscriptions contain mundane or profane messages.

But although the runes functioned like any normal alphabet in most cases, we also know that rune-related magic did exist in history, and we have examples of it described in our mythological sources as well as in archaeology19.

What’s important to understand, however, is that none of these descriptions of pagan-era rune magic work the way rune magic allegedly works according to many modern, esotericist authors who are uneducated in the actual history of runes.

A quick google search will yield lists of runes containing names and supposed magical meanings (Algiz for protection and “Inguz” for love, for example). But there are no attested examples of pre-Christian people using individual runes in association with these supposed concepts. In fact, individual runes are never attested as possessing any magical potency to affect anything all on their own.

With that said, runes are named for supernatural concepts, such as *ansuz meaning “god” and *tiwaz being the name of a particular god. But others represent very ordinary words like *ehwaz (horse) and *laguz (lake). In the same way we wouldn’t claim the letter “B” (which sounds like bee) is associated with flowers, honey, and fertility, attracting “swarms” of friends when worn on a pendant or used in magic spells, we have no reason to assume that runes worked this way in the pagan era either.

In every clear description of rune magic we have, runes are used as components within a larger magical formula. Typically this involves writing very particular sequences of runes in connection with performing other actions, and often requires the runes to be carved onto particular surfaces or materials, and sometimes painted as well. Additionally, when we do find a clear instance of a particular rune being used in connection with something like protection, it is typically not the rune we would have expected based on the way our modern minds associate concepts with the names of the runes (see below for an example).

What about bind runes?

The phrase bind runes makes these runes sound more special than they really are. Personally, I would have preferred calling them something a little clearer like combined runes. But here we are.

Historically, most bind runes don't have special meanings, but are normally just combinations of runes meant to be decorative or efficient. Let's take a look at some bind runes through the ages, starting with one from the early modern (i.e., after Christianization) period:

This wax seal from 1764 features a bind rune built from the runes ᚱ (R) and ᚨ (A). It was designed as a personal symbol for someone's initials. In this case, it's just meant to be decorative.

In the pre-Christian era, bind runes tend to come in three "styles", if you will.

Gibberish we don't understand and therefore might be magical or religious.

Efficiency techniques for carving where we usually don't see more than two runes combined at a time.

Decorative bind runes that manage to find creative ways to combine many letters together and still remain readable.

What follows are examples of each of these styles:

Seeland-II-C

The bracteate Seeland-II-C has a good example of a gibberish bind rune, containing 3 stacked ᛏ (t) runes forming the shape of a Christmas tree near the top-right. There are some guesses about what ᛏᛏᛏ might mean, and there's a good chance it has some kind of religious significance, but nobody really knows for sure. More importantly, it is very clearly a set of 3 "t" runes. We may not know what it's supposed to mean in modern times, but we can very easily read it.

The Järsberg Stone

The Järsberg stone is a good example of space-saving. It contains the Proto-Norse word ᚺᚨᚱᚨᛒᚨᚾᚨᛉ (harabanaz “raven”) wherein the first two runes ᚺ (H) and ᚨ (A) have been combined into a rune pronounced "ha" and the last two runes ᚨ (A) and ᛉ (Z/ʀ) have been combined into a rune pronounced "az". There is no special meaning in these bind runes, but combining them allowed the carver to save some space and a few lines. Again, the carving remains readable.

Södermanland Inscription 158

Södermanland inscription 158 is a good example of a creative bind rune that pulls together many runes at a time to spell out the phrase þróttar þegn (thane of strength). It’s written þ=r=u=t=a=ʀ= =þ=i=a=k=n from bottom to top. As always, there is nothing inherently esoteric or magical about this bind rune, but it is simply decorative. This particular style maintains readability by stringing all the letters out along a vertical line, rather than attempting to smash them all on top of each other.

In terms of established historical rules, the only real hard and fast rule seems to be that the reason something is being written is so that it can be read later, especially if it's on stone. Modern bind runes start to deviate from historical accuracy when they supposedly spell out words or ideas but are completely incomprehensible without explanation, for example in the following Instagram post labeled “Thors Bindrune of persistence” by Valhyr:

Note that I have no personal vendetta against Valhyr, whose artwork is actually incredibly good. This post just happened to come up near the top of a Google image search and it follows modern notions of symbolism rather than historical ones. The point is, we wouldn’t see this sort of thing from the time period when runes were in regular use because, after all, the whole idea is that someone should be able to come along in the future and be able to read and understand what you wrote. There is no way to see this symbol and read anything about Thor or persistence from it without having the creator explain to you their own personal system of symbolism.

Did pre-Christian people engage in runecasting?

Believe it or not, there are no explicit attestations of runecasting in the ancient Germanic record. However, we do have a couple descriptions of something that seems at least very close. In the 1st century AD, the Roman author Tacitus wrote the following account in his book Germania about the Proto-Germanic people living south of Scandinavia (as translated by Thomas Gordon20):

To the use of lots and auguries, they are addicted beyond all other nations. Their method of divination by lots is exceedingly simple. From a tree which bears fruit they cut a twig, and divide it into two small pieces. These they distinguish by so many several marks and throw them at random and without order upon a white garment. Then the Priest of the community, if for the public the lots are consulted, or the father of a family if about a private concern, after he has solemnly invoked the Gods, with eyes lifted up to heaven, takes up every piece thrice, and having done thus forms a judgment according to the marks before made.

It’s important to be clear that Tacitus does not tell us explicitly that runes were being carved onto the twigs. It’s certainly possible and perhaps even likely that the marks he mentions are runes, but it’s also plausible that they were not. With the recent discovery of the oldest known runestone, we can confidently say that runes were in use during the period when Tacitus wrote. At the same time, if we assume the described practice of divination had been around for a long time before Tacitus wrote about it, it’s theoretically possible that these could be marks that pre-date the introduction of runes into Germanic culture. In fact, what seems to be equally important as the marks is the fact that the divining material upon which they are carved is wood.

More wood-based divining shows up in the poem Hymiskviða stanza 121 when the gods need to select a good location for their feasts:

Ár valtívar veiðar námu, ok sumblsamir, áðr saðir yrði; hristu teina ok á hlaut sá, fundu þeir at Ægis ørkost hvera.

Early in time, the gods of the slain had a catch at hunting, and were feast-eager, before they were sated; they shook twigs and looked at sacrificial blood, they found at Ægir’s [home] cauldrons aplenty.

Unfortunately, we have no explanation for how shaking the twigs and looking at sacrificial blood ought to properly be done, and whether or not there are any runes involved. The poem Vǫluspá also associates prophecy with bits of wood in stanza 61 when describing conditions after Ragnarok:

Þá kná Hønir hlautvið kjósa, ok burir byggja brœðra tveggja vindheim víðan. Vituð ér enn, eða hvat?

Then Hønir can choose the lot-wood (sacrificial divining wood) and the sons of two brothers live in the wide wind-home. Do you want to know yet [more], or what?

The idea of “choosing the lot-wood” is entirely ambiguous with regard to what may or may not be carved onto the wood, but it does sound suspiciously similar to the practice described by Tacitus. In light of the social status Tacitus associates with this kind of divination, perhaps this stanza is meant to tell us something about Hønir’s status among the gods after the cataclysm. Or perhaps not. After all, Tacitus and Vǫluspá are separated by nearly a millennium.

In short, divining and “casting” of some kind does seem to be a part of the record, but there are unfortunately no modern guides about runecasting that are delivering any kind of accurate pre-Christian information on the details of how this practice works, simply because the information hasn’t survived.

You will also notice that every attestation of what appears to be “casting” involves bits of wood, never stones. This seems in line with the fact that Vǫluspá stanza 20 describes fate as being carved into wooden planks by the norns. As we will continue to see, trees and wood are an extremely important theme in ancient Germanic magic and religion.

What are some clear examples of rune magic?

There are many descriptions of rune magic in the Norse mythological sources but perhaps the most extensive collection of pre-Christian, rune-related spells is preserved in the poem Sigrdífumál in the Poetic Edda. In this context the hero Sigurd has just rescued the valkyrie Sigrdrifa (also known as Brynhild) from a magical sleep-curse placed upon her by Odin, and she proceeds to give him advice about useful magic spells.

In stanza 2, Sigrdrifa notes that “Odin caused that I could not shake off the sleep-staves”, indicating that even the supernatural effects produced by the chief god himself are sometimes wrought by rune magic. Then in stanza 5, she offers Sigurd a beer which she claims is “full of leeds (magical poetry) and helpful staves, good magic and pleasure-runes”. Finally, in stanzas 6-13, she explains a few spells Sigurd should learn. Here are two of them, from stanzas 6 and 10:

6. Sigrúnar þú skalt rísta ef þú vilt sigr hafa, ok rísta á hjalti hjǫrs, sumar á véttrimum, sumar á valbǫstum, ok nefna tysvar Tý.

10. Brimrúnar skaltu rísta ef þú vilt borgit hafa á sundi seglmǫrom; á stafni skal rísta ok á stjórnar blaði ok leggja eld í ár; era svá brattr breki, né svá blár unnir, þó kømztu heill af hafi.

6. Victory runes shall you carve if you want to have victory, and carve them on the the sword’s hilt, some on the battle-boards?22, some on the slaughter-cords?, and name Tyr twice.

10. Surf-runes shall you carve if you want to have sail-horses (ships) protected in a sound (i.e., at sea); on the stem shall they be carved and on the stern blade (rudder) and burned into the oar; the breaker isn’t so steep, nor the waves so blue23, that you won’t come home whole from the sea.

Following these spells we are given a short story relating their origin in which the disembodied head of Mimir advises Odin to carve runes into various objects which are then shaved off and stirred into sacred mead. These, according to stanza 19, are book runes, protection runes, ale runes, and various might/power runes “for anyone who can have them, unconfused and unspoilt, for himself as amulets; use [them], if you learn [them], until the powers (i.e., the gods) are ripped apart.”24

In each of the examples given, the choice of runes and method of inscription can not be arbitrary. If Sigurd desires safety at sea, he must carve brimrúnar (surf-runes) into the ship’s stem and rudder, and burn them into the oar. For a spell to be effective, using the right sequence of runes is important, their placement is important, and the method of inscription is important. This is well confirmed by stanza 19’s requirement that these must be used “unconfused and unspoilt”.

There are a few other fascinating hints at the wider system here as well. Apparently these types of spells are available to anyone who can learn them (as opposed to some exclusive class of magic user) and also appear to have an expiration date on their effectiveness, specifically the moment where the gods (and perhaps most specifically Odin) are destroyed at Ragnarok.

On the subject of Odin deriving some of his own power from runes, and backing up the idea that rune magic sometimes involves painting the carved runes, we can turn to Hávamál 157 wherein Odin is explaining a list of magic spells he knows:

Þat kann ek it tólpta: ef ek sé á tré uppi váfa virgilná, svá ek ríst ok í rúnum fák at sá gengr gumi ok mælir við mik.

I know it, the twelfth: if I see a hanged-corpse swinging up in a tree, I so carve and color in the runes that the man walks and talks with me.

In fact this magical cutting and coloring formula pops up in a few other places throughout our sources, including twice more in Hávamál, clueing us into an important theme. Most commonly, runes seem to have been painted red. This is made explicit in Guðrúnarkviða in forna stanza 22 when Gudrun is given a drinking horn covered in “all kinds of runes, cut and red-colored”, as well as in Egils saga when Egil is given a poisoned drink but he neutralizes the poison by cutting runes on his drinking horn and painting them with blood from his own hand.

Can runes be used for dark magic?

If we consider dark magic to be things like curses, then yes. In the poem Skírnismál, ten out of forty-two total stanzas are dedicated to a magical curse laid by Frey’s servant Skirnir upon the jotun woman Gerd, which culminates in the carving of runes. Beginning in stanza 26, we are given a large list of components (apart from the runes themselves) that go into making this an effective curse.

Skirnir first threatens to strike Gerd with a tamsvǫndr (taming wand) which appears to be a twig taken from a sap-rich tree that he found in the forest. Next he enumerates all of his horrible intentions for her, including being made a captive and a spectacle to be stared at, madness, affliction, unbearable desire, grief, oppression, misery, and various other torments. He then bookends his intentions with another reference to a gambanteinn (magic twig) which he has obtained from the forest, and is likely the same item earlier called a tamsvǫndr.

Next, Skirinir calls upon the wrath of a specific trio of gods, namely Odin, Thor, and Frey. It’s worth noting that these three appear together as idols in a pagan temple at Uppsala in an 11th-century account25 by Adam of Bremen, and the same three sit as judges together in the myth about the creation of Thor’s hammer. Their appearance together again here is probably not random.

There appears to be some evidence that in order for a curse to be effective, it needs to be noticed by the supernatural community. This idea shows up a few times in our sources and is illustrated here as Skirnir calls for the attention of all the gods and jotuns, presumably to make them aware of the fact that a curse is taking place. From stanza 34:

Heyri jǫtnar, heyri hrímþursar, synir Suttunga, sjálfir Ásliðar, hvé ek fyrbýð, hvé ek fyrirbanna manna glaum mani, manna nyt mani!

Hear, jotuns, hear, frost-thurses, Suttung’s sons, the Æsir-host yourselves, how I forbid, how I ban merriment in men from the girl, enjoyment of men from the girl.

Finally, Skirnir tosses in a few more torments and then seals the effectiveness of the curse by carving runes, possibly into the wand/twig he got from the forest. From stanza 36:

Þurs ríst ek þér ok þrjá stafi: ergi ok œði ok óþola; svá ek þat af ríst, sem ek þat á reist, ef gørask þarfar þess!

“Thurs” I carve for you and three staves: “perversion” and “frenzy” and “unbearable lust”; so I will shave it off as I have carved it on if reasons are made for this.

In other words, Skirnir seals his curse by carving the runes, yet the curse can be undone simply by shaving the runes back off, assuming Gerd will submit to his demands.

Note that while there is a single rune whose name is þurs (ᚦ), there is no single rune named ergi (perversion), œði (frenzy), or óþola (desire). Though óþola seems at face value to be similar to the name of the Elder Futhark rune ᛟ (*ōþala-), the meaning of this word is entirely different in Old Norse and there is no Younger Futhark rune bearing a similar name. Indeed there are no runes whose names even allude to these concepts so it seems that when Skirnir carves “three staves” here, he may actually be carving three full words. On the other hand, it’s also possible that Skirnir has associated these concepts with a certain three individual staves that are not obvious to modern readers based on their names. In any case, note that all of the concepts he has chosen to represent in runes call back to specific torments his curse intends to inflict upon Gerd.

How is modern rune magic different from ancient rune magic?

The most important point to understand here is that guides for performing Norse-themed magic found online or in books by esoteric authors all have their roots in 16th-century occultism at the earliest. By that point in history, the practices and rituals of Norse paganism had already been lost for centuries. This is not a statement about whether or not you should incorporate this kind of thing into your own spirituality, but just a reminder that there is no continuity of ancient Norse magical practices stretching from the pre-Christian era on into modern times.

A good example comes to us in the form of Sigtuna Amulet I which contains a historical pagan charm written in runes, and which I have also discussed in my post “The Thundergod is Humanity’s Hero.” For some context, here is the text of that amulet in English:

Thurs of sore-fevers, lord of thurses, flee now, you are found. Have yourself three torments, wolf (metaphorically, “monster”). Have yourself nine needs, wolf. With these "i" runes, "iii" (used here as a magical incantation), the wolf is appeased. Enjoy healing!

This artifact illustrates how the modern mindset typically does not match up with the ancient mindset when it comes to spirituality and magic. Specifically, the rune used in this context to invoke protection from monsters and thereby catalyze healing from physical disease is the Younger Futhark “i rune” (ᛁ) herein called íss (ice), which descends from the Elder Futhark rune also named for ice.

A quick online search for “meanings of the runes” will (at the time of this writing) not yield results naming ᛁ as a protection rune. Normally, that role is reserved for ᛉ (presumably because elk are defensive creatures and the name of this rune might be related to elk). Rather, because ᛁ is named for ice, the modern mind associates it with things like pauses, stasis, inertia, waiting, and various other symbolic ways of describing the idea of being frozen. There is no obvious link from our vantage point in the twenty-first century between ice and and protection from monsters, so we instead rely on modern associations to assign meanings to the runes. Yet it is ᛁ, in a sequence of three, that we find being used in exactly this way in the actual record from the Norse period (and, of course, no record of ᛉ symbolizing protection).

Why was a sequence of three “ice” runes chosen to ward off an attacking lord of thurses as opposed to, say, the ás rune (ᚬ) which is named after the gods themselves? For that matter, why does Sigrdrifa associate nauðr (ᚾ) with “ale-runes”26 and magic that prevents the betrayal of trust by someone else’s wife? Unfortunately, we just don’t know. But what this sort of thing indicates is that we are very unlikely, with our modern minds, to be able to properly analyze the runes and come to any sort of conclusion that is anywhere near the way pre-Christian, Germanic people would have used them for magical purposes a thousand years ago. But personally, I think that just makes the puzzle even more exciting.

Available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Runic-Amulets-Magic-Objects-MacLeod/dp/1843832054

Available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Runes-Handbook-Michael-P-Barnes/dp/1783276975/ref=sr_1_1

More from the University of Oslo’s Museum of Cultural History: https://www.khm.uio.no/english/news/found-the-world-s-oldest-rune-stone.html

Pettit, E., trans., The Poetic Edda: A Dual Language Edition, (Open Book Publishers, 2023), p. 97, 113.

Page, R. I. Runes. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1988.

Barnes, Michael P. Runes: A Handbook. The Boydell Press, 2012.

Page is hesitant to provide a name for this rune based on the fact that the rune poems disagree. Barnes (2006) settles on *kauna, which I have accepted here.

The ᛦ rune signifies an evolution of the Proto-Germanic “z” sound which was earlier written with ᛉ in Elder Futhark. In later Old Norse pronunciation, this sound merged with “r”, but prior to merging must have been pronounced somewhere between “r” and “z”, which is often signified in Latin-letter transliterations as ʀ.

The reason for this is that Old Norse “v” evolved from an earlier pronunciation that sounded more like English “w”. In the earlier stage, the “w” sound was considered similar to a rounded vowel.

Introduction information at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalecarlian_runes

For example, the runestone Ög 43 is written in Younger Futhark but makes use of a single ᛞ rune to stand in for the full word dagr (day). https://www.raa.se/app/uploads/2019/02/%C3%96g-43-Ingelstad-%C3%96stra-Husby-sn.pdf

See, for instance, Jackson Crawford’s explanation of how the carver of the Rök runestone appears to misunderstand some of the differences between the Elder and Younger futhark systems.

Introductory information at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lindholm_amulet

Introductory information at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Velanda_Runestone

Introductory information at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R%C3%B6k_runestone

Introductory information at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Runic_inscriptions_in_Hagia_Sophia

Documented here: https://www.runesdb.eu/find-list/d/fa/q////6/f/3070/c/88405dfbbc324e5842d4d7991cba29e1/. Note, however, that at the time of this writing, runesdb.eu appears to be having SSL Certificate issues and may be flagged by your browser as an unsafe connection.

See, for example, my post “The Thundergod Is Humanity’s Hero”.

Translation available online from Fordham University: https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/tacitus-germanygord.asp

Though the English translations are my own, I am using Edward Pettit’s Old Norse transcriptions and stanza organization. (Pettit, E., trans., The Poetic Edda: A Dual Language Edition, (Open Book Publishers, 2023))

The words vettrimum and valbǫstum are obscure so I am passing along Pettit’s (p. 525) translation of these words here. Pettit includes a note (p. 533) explaining that, while obscure, these are terms for parts of a sword, possibly referring to some kind of metal plate or ring, and a winding around the grip.

The blueness of the waves here is a play on the fact that the word blár is also used as the color of death in Old Norse.

Pettit, p. 527

Tschan, Francis., trans., Adam of Bremen: ‘The History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen’. New York. Columbia University Press. 1959.

Pettit, p. 525